I Found a Penny Today, So Here’s a Thought

|

|

|

|

|

|

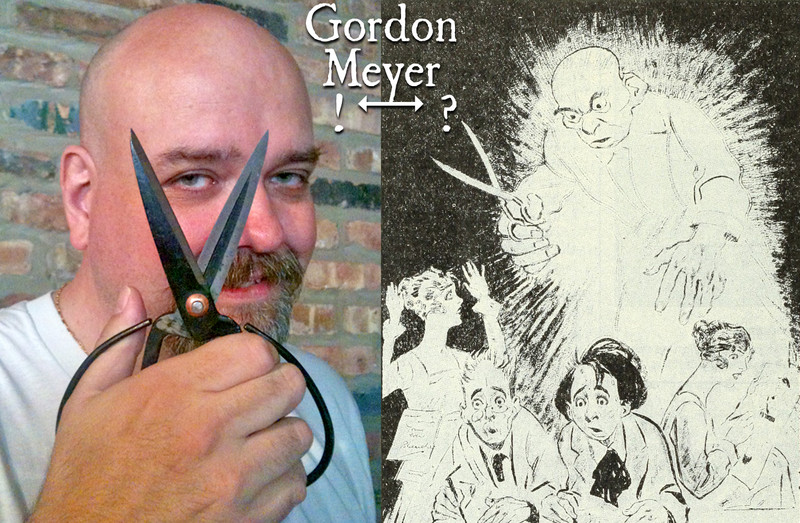

When we learned that our favorite website, Long-Forgotten Haunted Mansion, was drifting into a peaceful slumber, our first wish was that the site forever spook but never petrify. (See our anagram.) But the site's intrepid investigator, HGB2, offers some anagrams of his own:

As Long-Forgotten slumbers on in a state of hibernation, you may begin to feel melancholy and alone. I would suggest going out into that serene and lovely front yard, letting the grass and the trees restore your spirits. In other words, if you yourself feel long forgotten, our advice is: Go to front glen.

On your way out, as you leave the building, you might mutter absentmindedly—and with perhaps with a hint of bitterness—the cliché, "Last person out, turn off the lights," forgetting that there's no electricity in the world of the Mansion. Amused, we remind you: No front toggle.

If we allow it, this may recall to our minds that it isn't the technology that charms us, but simple, timeless tricks and illusions. So easily we forget that it's an old-fashioned magic show: Forget not long.

(See why we shudder at the thought of Long-Forgotten going on hiatus?!)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

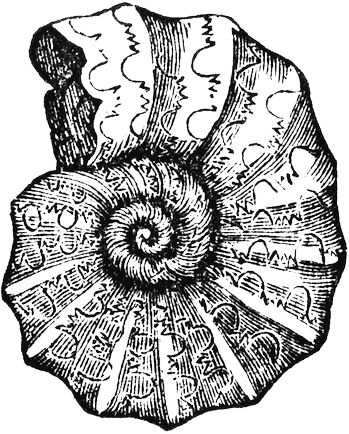

This manual seems to titularly announce its target demographic, but don't let that fool you. It's like reading Lewis Carroll. No matter how much weariness there is in your bones, the sprite of your mind will fly with and to these words.

It's lavishly illustrated by the author with all sorts of abraxases and magic squares and mystical beasts whose mix-and-match bodies were the precursors of today's recombinant, genetic portmanteaux.

How much ... a delight it is ... to simply enjoy the uncommon truths of these eldritch spells coiled upon themselves and their secrets like wonderful chambered nautiluses.

The book elevates sound (and its magical properties) to the same level the Theosophists did, but in a much more playful way. It is a preposterous work, in the best sense of that word.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Anonymous asks, "If I may, I was told I have to find my voice. Any ideas? Suggestions?"

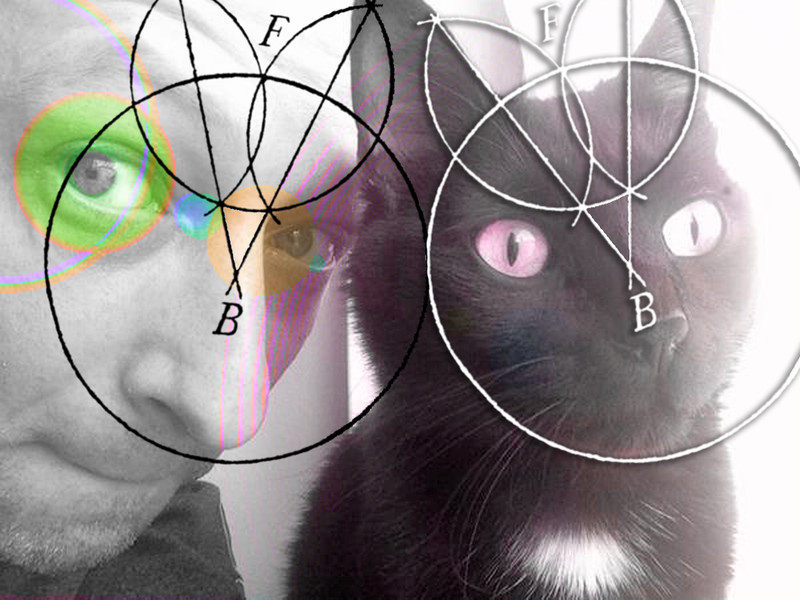

This vintage diagram explains all. [Its context is technically unrelated (you may or may not recognize its original purpose), but no matter.] We see the form of a lower-case i, and that's crucial. Note that the lower-case i has a head on its shoulders, unlike the capital I, which is merely a construct (a girder and two beams, eh?). And so the capital I/ego decapitates the genuine expression of the little i. The dot of the i makes this diagram a universal "You are here" map. One's voice can never to be "found," for it's impossible for it to go missing. It's always here, at ground zero. The question can only be, what has been overlaid and is hiding that dot? Is it a respected voice one has been emulating? Is it an artificial attempt to meet perceived requirements or expectations? Emulations refer to the past, and expectations allude to the future. It's only in the eternal present moment that one's unique voice resonates. In terms of writing projects, it's perhaps most difficult to express one's true voice in an assignment or an homage. The key is to work on a project so idiosyncratic that there are no precedents. (For example, we recently challenged ourselves to come up with a guide to The Care and Feeding of a Spirit Board. Nothing even remotely like it had ever been written, so it was unexplored territory where no other voices echoed.) That's the key, but it's a trick key, and the trick is to allow yourself to get so caught up in the current of writing that your capital I gets left behind. But forget all that -- the vintage diagram says it better.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

On the basis of two bits of evidence (but please send us more examples), we've determined that British humo[u]r can move any mountain (to the tune of The Shamen's "Move Any Mountain" or not). Exhibit A: In Maurice Dolbier's Nowhere Near Everest: An Ascent to the Height of the Ridiculous, we find a character who boldly "contrived the removal of Mount Everest and the substitution of a smaller peak, in an attempt to create an international incident." Exhibit B: In the series one, episode two of Absolutely Fabulous, a character is sued by British Heritage for shifting some ancient standing stones out of the way:

Eddie: Sued? Why are being sued, darling?

Bubble: Well, that last fashion shoot you organised. Apparently, someone moved a couple of rocks, or something.

Patsy: Moved a couple of old rocks? My God!

Eddie: Stonehenge, Pats. Anyway...

Patsy: So? They should be glad of the publicity.

Britain's effortless ability to move any mountain through humo[u]r is unmistakable.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

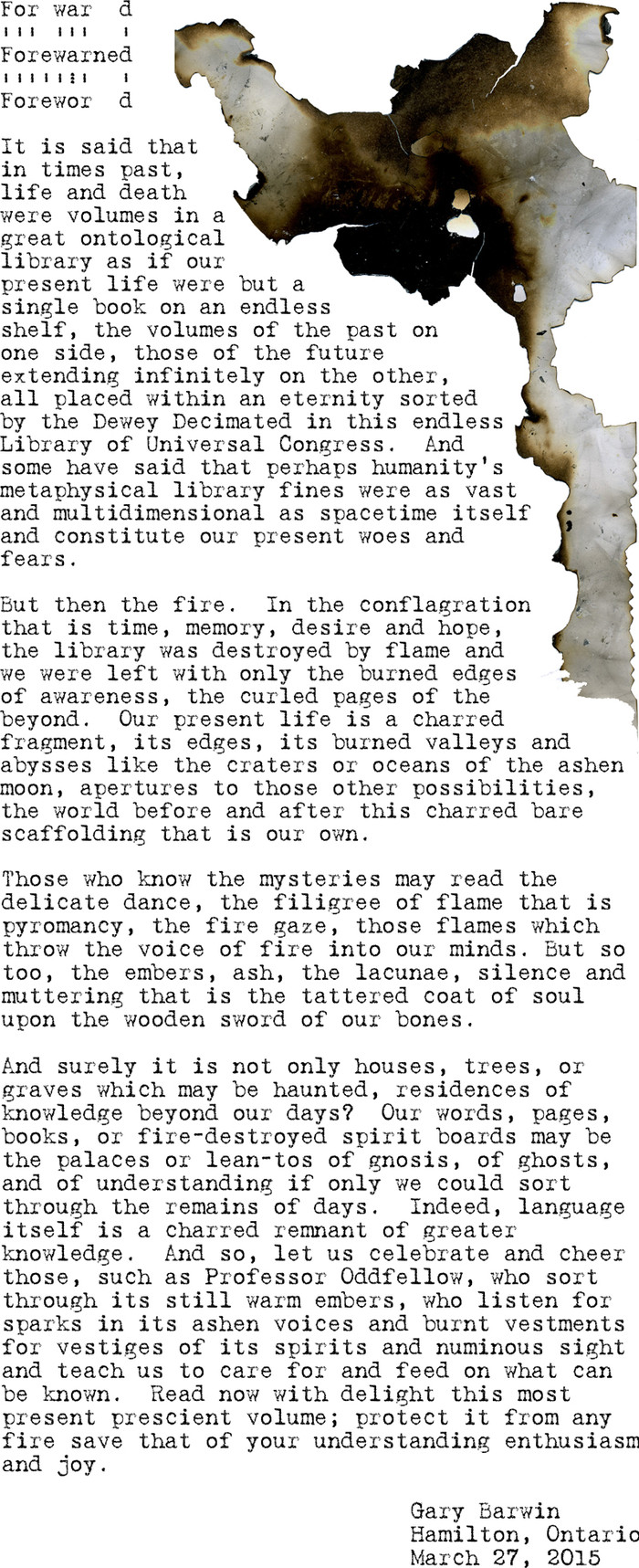

Can one judge a book by its first page? (Spoiler: we do.) We bought Kazuo Ishiguro's The Buried Giant after reading John Pistelli's piece about it, and we'll probably try to get through it, but page one sure did leave us cold. (That's not counting Ishiguro's blatantly misused semicolon in the second line.) We're initially astonished over the banquet of praise the book has received. In fairness, one can't help but to draw comparisons to John Cowper Powys' astonishing Porius, which similarly explores ancient Wales and its mythology (only Powys, under the spell of Merlin, writes sublime sentences from the get-go). Almost more so, we're still staggering from the utter brilliance of The Attic Pretenders, which presents itself as an actual artifact of the Otherworld (and may be the only one of its kind: the phrase "artifact of the Otherworld" delivers zero Google results). (And thanks to Writers No One Reads for putting us onto The Attic Pretenders.) Compared to the visceral Otherworld that Attic Pretenders captures, the first page of The Buried Giant feels like a child's chalk drawing. While we'd love for page two of The Buried Giant not to disappoint, we have entire color-coded bookshelves of vastly better-written prose.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

(This is our submission to Writers No One Reads, which is where we first learned about our very beloved The Secret Service by Wendy Walker.)

No one reads fine artist Rhea Sanders' guidebook to the fictional Fire Gardens of Maylandia or Sweetwilliam's Folly (The Tradd Street Press, Charleston, SC, 1980). The author respectfully dedicates this wryly humorous, meticulously envisioned oddity to "the virus which gave me the fever which gave me the hallucination which gave me the idea for this book." The reader of the deadpan guidebook is presumed to be a tourist to the state of Maylandia, in possession of a working knowledge of local attractions, so the mysterious nature of the fantastical fire gardens is revealed in subtle tidbits as the site's colorful and often controversial history is explored. We learn that the gardens were conceived in 1720 by the first royal governor, Ferdinand Mayland, "during one of his annual bouts with a local fever." The author dryly recounts how the governor persuaded the indigenous Changapod tribe to relinquish their sacred plains of flaming shale at the foot of the mountain they called "He Who Waits": "Since all objected, all were done away with. This is indeed a sad episode, but it is well to remember that the Changapods had owned this territory for centuries, and had done nothing with it, whereas Governor Mayland imagined a work of art. There were in any case only 370 Changapods." As the history progresses, we become privy to intimations of "fireworkers" in possession of "the knowledge" -- carefully guarded secrets of controlling the shape, movement, and color of fireballs, handed down from father to son over generations. We learn of figures with oddly Francophilic inclinations, such as the Governor's London-born wife Marguerite, who "spoke only in French, for reasons which have not come down to us." We learn of the possibly addictive tea leaves that grow near the fire gardens and seem to treat the blue skin condition resulting from exposure to the natural gasses. ("And why should everyone be either black, white, red, or yellow?") We learn of several possible murders along the way, all unsolved, including one in 1927 -- the winner of a contest to name a new garden to express the spirit of the age. A certain Billy Jackson's entry, "Jazz Baby," earned him a $5,000 check, though he was shot and killed on his way home and the check stolen. "We in Maylandia often point to Mr. Jackson's Jazz Baby Garden when outsiders ask us about the minorities in our midst. For what could be a more beautiful testimonial to our treatment of minorities than this Garden?" We learn of tea plantation heiress Angela Longleaf MacDowell, who stood six feet tall and boasted, "No man on earth or beneath the sod has ever kissed the lips of Angela Longleaf MacDowell." It was she who envisioned, in a dream, the memorial fire garden for famed local poet Cassius Augustus Robertson ("the story of Robertson's mysterious death at the age of 99 is too well known to be recounted here"). Profusely illustrated by the author, The Fire Gardens of Maylandia is a charming, deeply funny, and thought-provoking relic from an alternate reality just a little bit more smoldering than ours. (Profuse thanks to Hilary Caws-Elwitt for recommending this book.)

|

Page 142 of 170

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2025 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|