|

Your Own Self-Assembling Divination Deck

by Craig Conley, a.k.a. Prof. Oddfellow

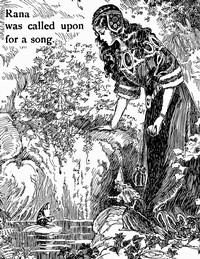

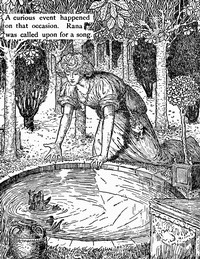

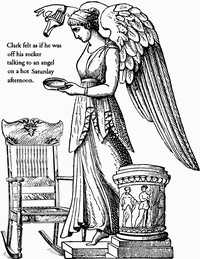

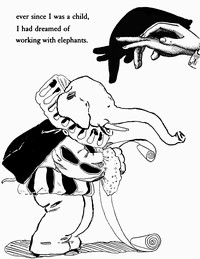

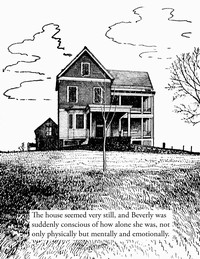

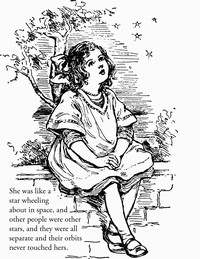

One of the best-kept secrets of cartomancy is that anyone may have an eerily personalized, fully illustrated deck of illuminating archetypal imagery and divinatory statements that virtually assembles itself. Even non-artists, non-writers, and the prophetically-challenged are eligible. The key is a certain sort of public domain book, technically on an unrelated topic and therefore the perfect preserver of the secret. With a little old-school cutting and pasting onto index cards (the preferred method) or some higher-tech scanning for glossy print-on-demand decks, a one-of-a-kind soothsaying system will manifest before your eyes as if you were a genie granting your own wish.

Here is the innermost chamber of the heart of the secret: we find our crucial material in old books of children's theatrical productions, full of time-honored, archetypal characters as well as illustrations (provided as guidance for costuming) and pithily-worded dialogue that, taken out of context, works rather amazingly as predictive aphorisms. Such books are freely available in the archives of virtual libraries, though a more exciting and providential method is to discover one in an antiquarian shop's dramaturgical corner.

To give a sense of the sorts of material one may pull from, consider these evocative casts of characters found in The Magic Sea Shell and Other Plays by John Farrar, 1923. One may choose a particular character from one play and others from separate plays, as certain names and imagery spark intrigue. It's an intuitive process that is completely natural and effortless. When a particular figure calls to you, you'll most certainly notice it.

The Spirit of the Shrine

A Child of Pan

The Mikumwess, an Indian Elf

The Spirit of Dreams

The Spirit of the Wind

The Spirit of the Forest

The Spirit of Mischief

The Spirit of Sport

The Spirit of Youth

The Moon

The Sun

The Stars

The Clouds

The Winds

The Rain

Light

Fire

The Mountains

The Foothills

The Lily

The Pearl

Story-Book

Study-Book

The Old Man of the Sea

The Mermaid

The Sailor Boy

The Octopus

The Shark

Icicle

Old Man February

Lady Fair

Leap Year Baby

Cupid

Cavalier

Toadstool

Poison Ivy

Jack-in-the-Pulpit

Queen Wild Rose

Trumpet Flowers

A Man

Hate

Pain

Lust

Sin

Love

Sorrow

Hope

Despair

Death

Terror

Dead Dreams

Shadow of the Past

Will-o'-the-Wisp

The Shadow of a Man

The Shadow of a Woman

The Soul of a Child

The Shadow of a Dream

Elves of the Moonlight

Elves of the Starlight

The Wind

The Fountain

The Grass

The Dew

The Firefly

The Cricket

The Moth

The Beetle

The Rose

The August Lily

Sunflower

Moonflower

Johnny-Jump-Up

A Witch, Representing Mortal Sin

The Spirit of Evil

The Spirit of Good

A Woodcutter, Ignorance

A Little Boy and Girl, Representing Innocence

Lob and Hob, Ministers of Evil

A Demon in the Form of an Ape: the Witch's Familiar

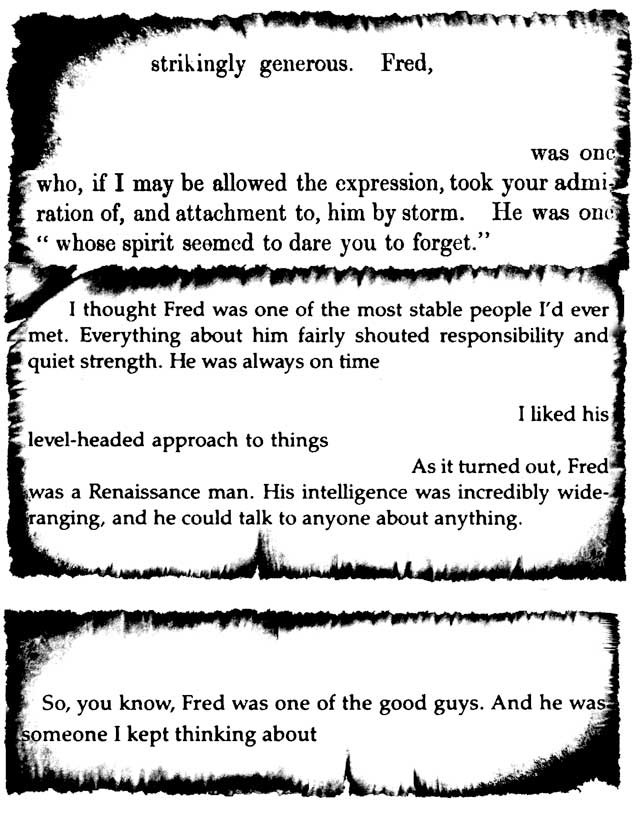

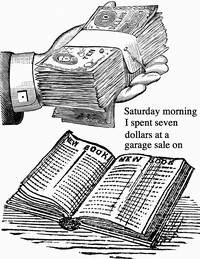

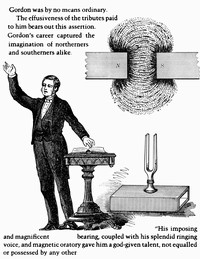

An Owl, a Cock, and a Cat: Imps

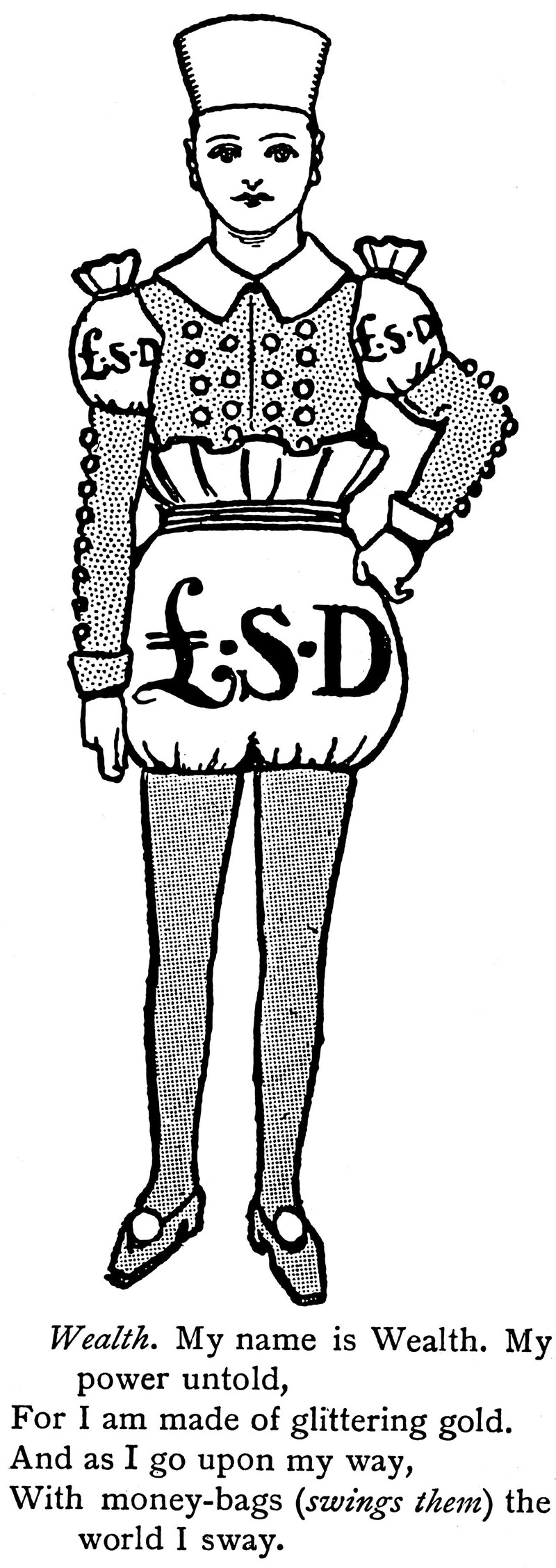

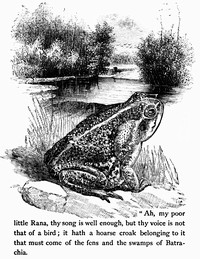

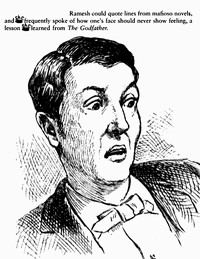

The construction of a deck will involve snipping the character's name, illustration, and a fragment of dialogue that seems to speak a universal truth or offers either an affirmation or a timely warning.Pictured here is the archetype of Wealth, from Home Plays by Cecil Henry Bullivant, 1911. He's not quite as psychedelic as he might appear at a glance, for the "LSD" actually refers to Britain's pre-decimal monetary values of "pounds, shillings, pence," from the Latin "librae, solidi, denarii." He comes complete with a quatrain of dialogue that identifies his influence: "My name is Wealth. My power untold, for I am made of glittering gold. And as I go upon my way, with money-bags the world I sway."

As other examples of pairing dialogue to characters, the play featuring Dead Dreams has them say: "Let us in. We freeze. Why have you barred us out? Our wings are torn, and our long hair drops constantly with rain." Such a statement could encourage the querent to recall an aspiration that was somehow forgotten or otherwise abandoned along the way. The character Hope offers a very positive promise: "Fear not. Be comforted. Peace keep thy soul. Despair and Grief can touch thee never more." The character Love has this heartening message: "Have courage. Death is swallowed up in me." The character Evil counsels to burn away that which offends you: "Let fire have its way. Strew it around. … Let it rage and roar. Sow its red seeds about, and let them spring and blossom crimson to the crimson moon."

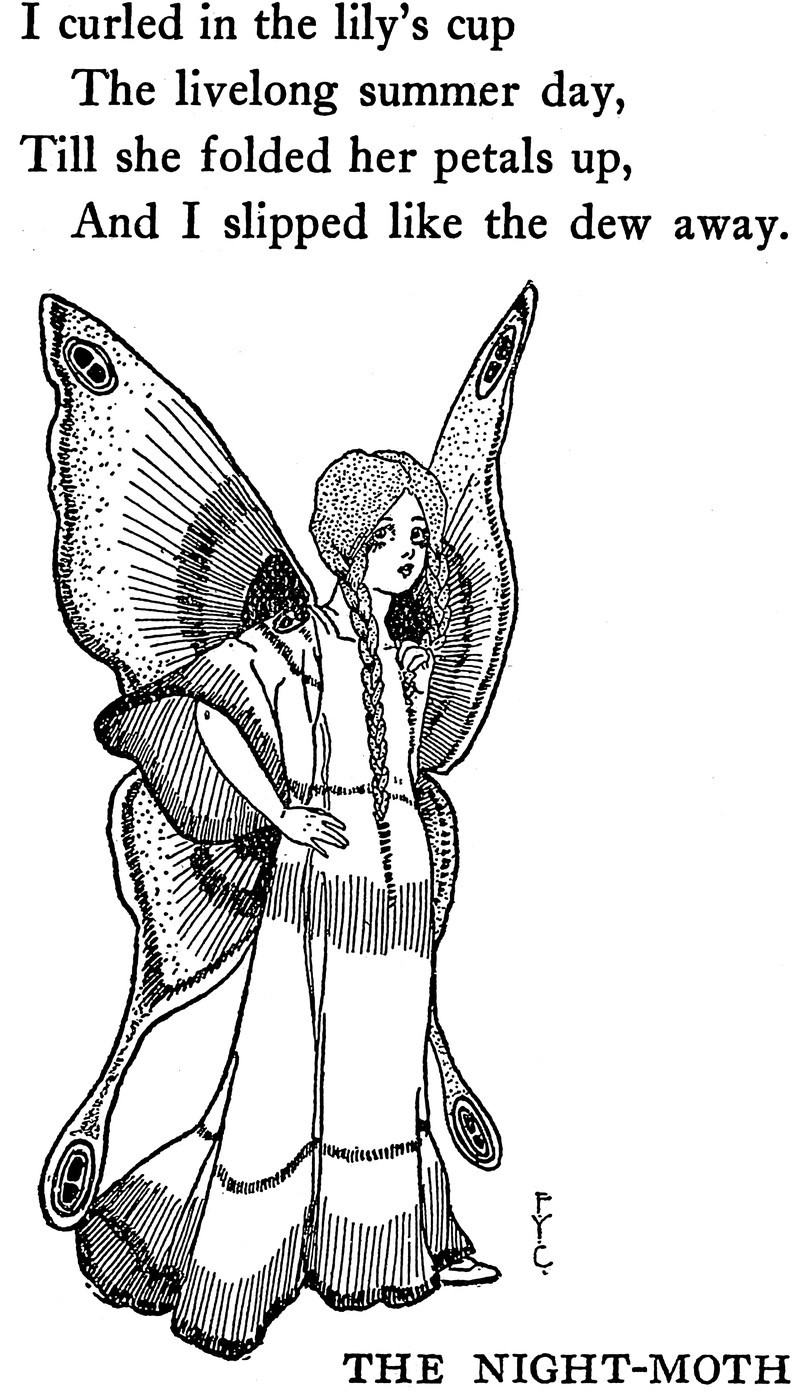

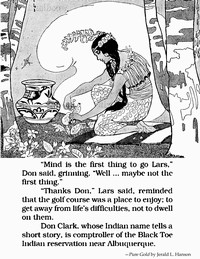

Consider this sample card featuring The Night Moth, from the St. Nicholas Book of Plays and Operettas, 1905. The moth fairy says that all through the summer she curled within the petals of a lily, and when the lily finally withered, she slipped away like dew. This could serve as a reminder to take advantage of and enjoy resources while they last, then move on when an inevitable cycle comes to fruition.

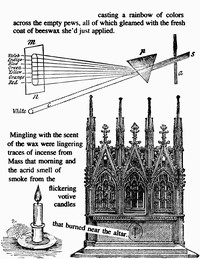

Dialogue is one thing, but one may also include interesting stage directions from a script. Here are some examples from The White Christmas and Other Merry Christmas Plays by Walter Ben Hare, 1917: "Lights all on full." "Low rumbles of thunder are heard." "Ghost exits unseen." "The cheers are given." "Soft chimes. As these chimes die away in the distance a concealed choir is heard singing."

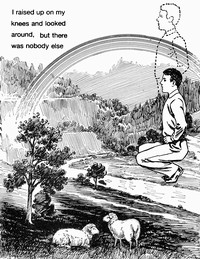

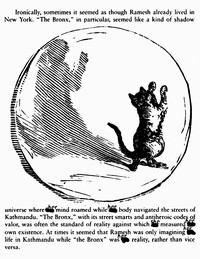

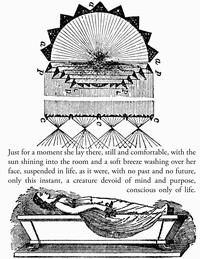

Pictured here is the Spirit of Dreams (The Magic Sea Shell and Other Plays), who blows and tosses a large bubble. As a fortune telling card, she might encourage one to "sleep on it" and make a decision the next day. Her line, "Bubble! Bubble! Whither flying?" might direct one to pay attention to "which way the wind blows" in the sense of discovering information about a situation before taking action.

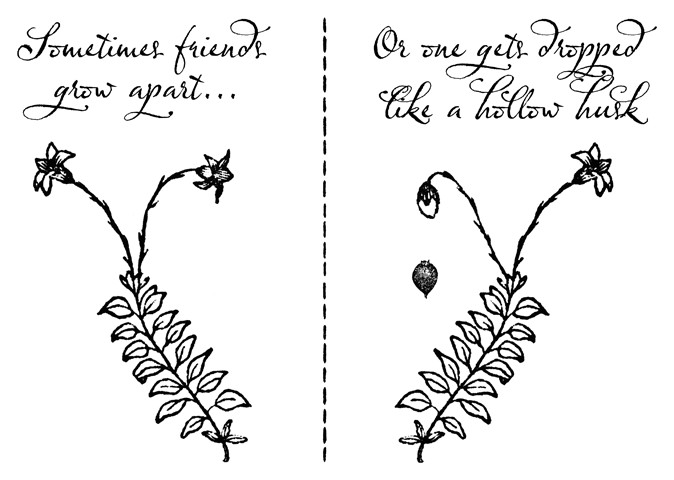

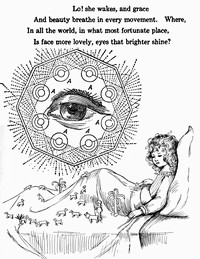

Rather than ask a particular question, the preferred way to use this sort of divination system is to first think of a short title for the personal drama in which you find yourself. There’s no incorrect way to do this — simply attempt to encompass your situation in two to four words. “What Happens in Vegas” might be an appropriate title for concerns about an upcoming vacation to Nevada. “A Question of Romance” might serve if you are worried about a love interest. “The Agreement” might be a title involving a commitment or a contract. “All Through the House" might denominate a domestic issue. “Hurry Up and Wait” might address a particular limbo. “What Goes Around” might be an appropriate title for a reading intended to identify what’s about to come around. “Cat and Mouse” might be appropriate for thwarting an opponent. “The Promotion” might name a work-related issue. For a more general reading, try a broader title like “That’s Life” or “The Way of the World.” Once you have settled on a title, draw cards to initiate your character set and script. Every reading becomes a unique script to shed light upon one’s particular situation. That’s because “Theatre reveals what is behind so-called reality” ( The Cambridge Introduction to Theatre Directing, 2013) and also because a text “exists only as an event that reveals the reader’s self” (James Machor and Philip Goldstein, “Theoretical Accounts of Reception,” in Reception Study, 2001). A spread of cards with snippets of conversation forms its own miniature script. How could a collaged dialogue make sense? “A text can make sense and someone can make sense of a text. If a text which at first did not make sense comes to make sense, it is because someone has made sense of it” (Jonathan Culler, The Pursuit of Signs, 1981). “We make sense of a text by relating it to the context of our knowledge, emotions, and experience. But since such contexts will be different for particular readers, so interpretations will vary also” (Peter Verdonk, Stylistics, 2002). Deconstructionism “holds that a reader is free to find meaning in a text that the writer did not intend and — in making the interpreter a partner in the creation of copy — seeks to replace the stability of logic with the fluidity of paradox” (William Saffire, No Uncertain Terms, 2004). The composition of the cast of characters may offer important insights into the nature of your reading. For example, is there a “cold” tone to the scene with figures like Jack Frost, Santa, or a tin soldier? Are several grandparents and other elders present, indicating wisdom or authority? Is there a preponderance of mothers and nursemaids to suggest nurturance? Have mysterious or frightful spirits and ghosts made themselves known? Do children predominate, suggesting naivety or new beginnings? Are several Irishmen present, traditionally associated with luck? Musicians may appear, suggesting the importance of timing and harmony. Clowns might also congregate, to lighten the tone. Characters might hold walking sticks or crutches, indicating sources of support. If any carry umbrellas, they're prepared for inclemency. Look also at the directions characters face. Are most or all facing left, or right, or forward? Such alignments may be meaningful to your situation.

Old books of theatrical entertainments for children (like Let's Pretend: A Book of Children's Plays by Lindsey Barbee, 1917) are treasure troves of quintessential personae who spring from our deepest wells of folk wisdom. They are preserved in a liminal space, a threshold of time. Over long centuries they have continued to surface in retellings and re-imaginings of humanity's profoundest narratives. There is no one "right" or "wrong" combination of such figures. We conjure characters from old plays as portentous ghosts of holy days past, in the grand tradition of Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. This system brings to life forgotten characters from plays that may no longer be performed on stage, and their scripts are newly invigorated via a process of natural selection as we combine disparate dialogues into literally cutting-edge creations. Though we call these characters ghosts, they are more accurately archetypes, which are “neither entirely natural nor super-natural” (Derek Steinberg, Consciousness Reconnected, 2006). Simply put, “An archetype is an awareness of what is yet unknown” (Cynthia Ashperger, The Rhythm of Space and the Sound of Time, 2008). To see us out, here's a character from The White Christmas and Other Merry Christmas Plays. He says, "For I'm the Wishing Man. I have wishbones on my fingers, I have myst'ry in my eyes, my clothes are trimmed with horseshoes, and they're stained with magic dyes. My pocket's full of rabbits' feet, and clover leaves and charms; for luck I've got a big black cat all tattooed on my arms." Good luck!

|