I Found a Penny Today, So Here’s a Thought

|

|

|

|

|

|

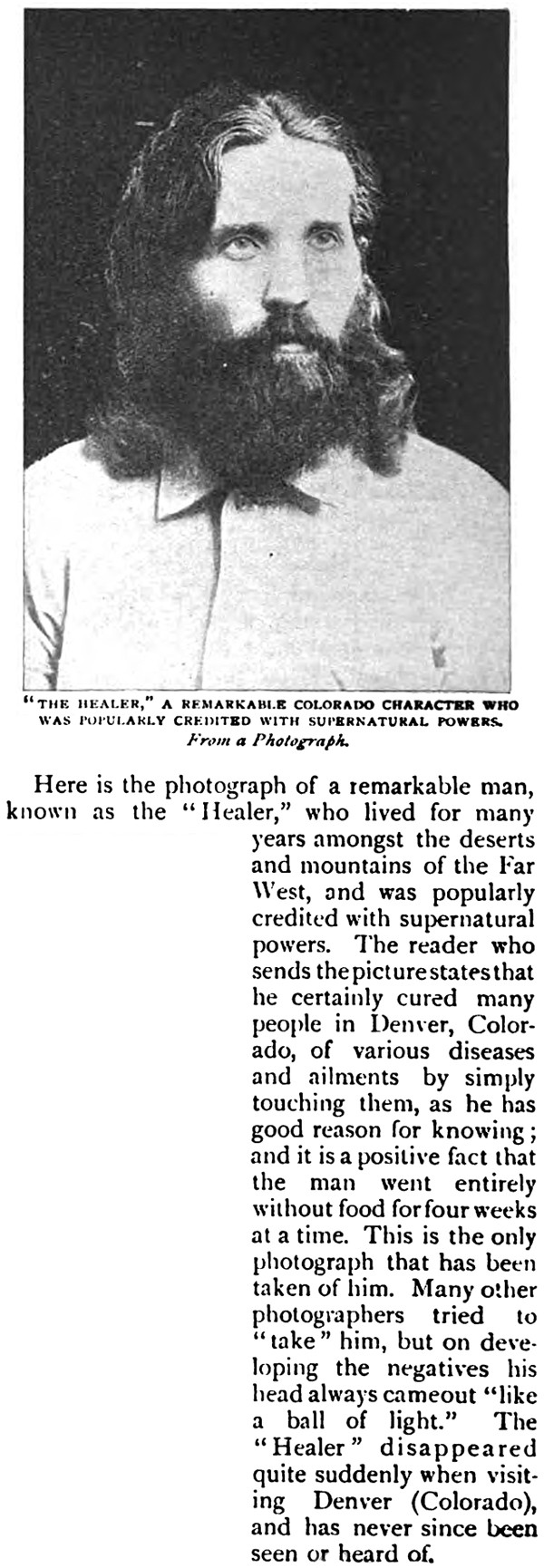

Why does humankind still grapple with the greatest questions? Why can we ultimately know nothing? And what, then, shall we occupy ourselves with? All is revealed here: "I have always been interested in the oddities of mankind. At one time I read a good deal of philosophy and a good deal of science, and I learned in that way that nothing was certain. Some people, by the pursuit of science, are impressed with the dignity of man, but I was only made conscious of his insignificance. The greatest questions of all have been threshed out since he acquired the beginnings of civilization and he is as far from a solution as ever. Man can know nothing, for his senses are his only means of knowledge, and they can give no certainty. There is only one subject upon which the individual can speak with authority, and that is his own mind, but even here is surrounded with darkness. I believe that we shall always be ignorant of the matters which it most behoves us to know, and therefore I cannot occupy myself with them. I prefer to set them all aside, and, since knowledge is unattainable, to occupy myself only with folly." — William Somerset Maugham, The Magician |

|

|

|

|

|

|

What a weird experience: my "fundial" doodad (which I discovered via Bernie DeKoven) was kaput, but then I realized that the only moving part was my own index finger. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

a hole in something what a card trick does to fingers

— Gary Barwin, "Because Birds" To our knowledge, only one person has thoroughly described what a card trick does to a magician's fingers. With each magical performance, the digitations are aroused to "borrow" or "liberate" according to new yearnings. Some fingers steal people's secrets, under the delusion that possessing elements of a personal life makes them one's own. Some steal other people's names, leaving in their wake individuals without any knowledge of who they were, forced to trust in the testimony of friends and relatives. Some steal time, with the logical intention of prolonging their days; they steal past time when in the mood to dwell upon memories; they steal present time when feeling constricted by immediate limitations; they steal future time out of the very lives of children when hard hit by the panic of impending dissolution. Some steal dreams, leaving others' sleep blank and uncharacterized. Some steal sleep itself so as to hibernate like a bear, leaving victims staring, on the verge of despair and madness, night after night in the indifferent dark. Some steal others' hope, though always leave just enough to keep them from suicide. We find these insights in Wendy Walker's masterpiece The Secret Service (1992), which we have here paraphrased. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Now here's a concept, courtesy of the wag (Jonathan Caws-Elwitt): The New York State Thruway service-area map lists which concessions inhabit each service area. Well, I'm calling them "concessions"... but apparently, in turnpike corporatese, a Starbucks or a McDonalds in a service area is called a "concept." Thus, the map's legend informs us that "24-hour concepts" appear in bold lettering.

So if you ever wake up in the middle of the night and you can't find the insightful paradigm, penetrating theory, or brilliant idea you came up with earlier in the day... maybe what you have there is a concept that's limited to bankers' hours or standard retail hours. (And if the concept comes and goes at peculiar times of day... well, maybe it's operating on a British pub-licensing schedule!)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

There's so much to love in this first page of William De Morgan's When Ghost Meets Ghost (1914). The first chapter is very rightly numbered zero. Shouldn't all ghost stories begin with chapter zero? The chapter summary is playfully honest about what it amounts to, and it mentions a "somewhere that is now nowhere." In the first paragraph, there's a withering mention of several young ladies having "lost their individuality." The third paragraph exposes a great truth: a story can do without accuracy. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

The brace pictured here marks the space of six seconds. It's a "thrill unit" (what Wendy Swanscombe calls a placet [Latin for "it pleases"]). From St. Nicholas magazine, 1904.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

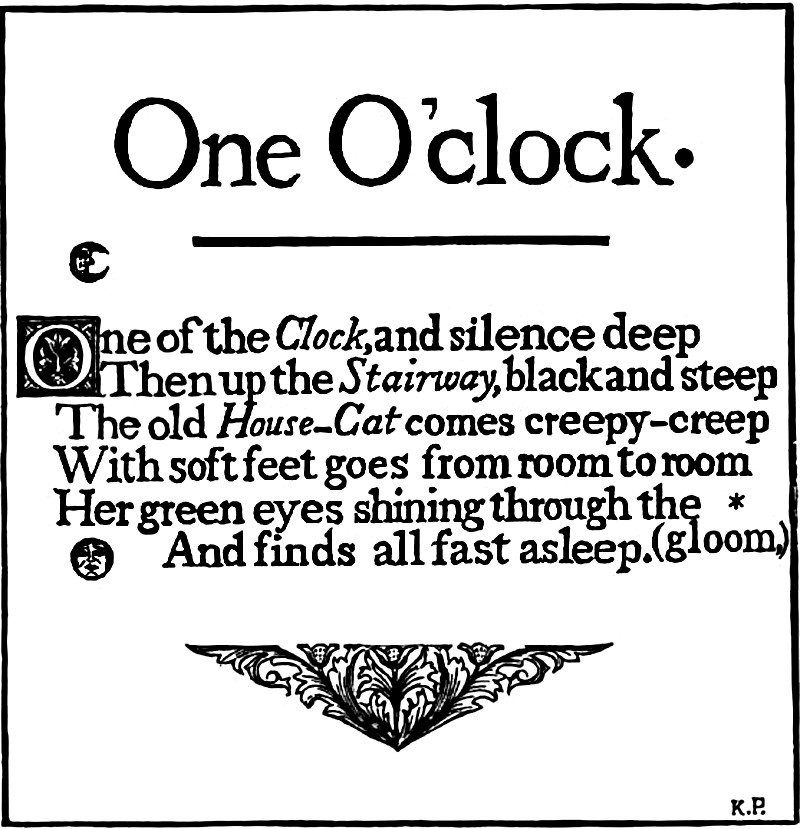

Our Favorite Asterisk of All Time?Check out the very special asterisk in this little verse from The Wonder Clock by Howard Pyle, 1887. It stands for the word gloom (in all fairness, how much clarity can we expect of gloominess?) even as it concentrates what little light there is into a gleam in a house cat's eye. Is the asterisk here a genuine example of visual poetry, or did the typesetter run out of space and improvise grandly? We don't care, as the result stands. (Note that we hunted down what would appear to be the web's only other gloomy asterisk, if only to give the cat's other eye a twinkle.)

"Asterisk + Gloom," a photo by Richard Weston, appears here in the context of literary analysis.

|

Page 147 of 170

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2025 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|