I Found a Penny Today, So Here’s a Thought

|

|

|

|

|

|

"For pygmies, if you don't fall down laughing, your laughter is incomplete."

—Enrique Vila-Matas, Montano's Malady |

|

|

|

|

|

|

by Nina HSeeing Colors Through Rose-Tinted GlassesThine is the heritage of the world, thine the task of moulding destinies, thine the privilege of seeing all things through rose-coloured glasses.

—Charles W. Wood, The Argosy

"To see the world through rose-colored glasses" is an idiom referring to a positive outlook colored by naivety or sentimentality. As feminist commentator Pamela Varkony puts it, "Looking at the world through rose colored glasses makes for a pretty picture, but not an accurate one." To be sure, one famous drawback of rose-colored glasses is that not everything that appears red is objectively red. Hence, the lovelorn are cautioned against wearing them: "When we are in love, or when we want to be in love, we sometimes see the world through rose-colored glasses and don't spot the red flags" (Christine Hassler, 20 Something, 20 Everything, p. 224). Sightseers are also advised against wearing rose-colored glasses while on holiday: in Alaska, you'll miss seeing the Northern Lights; in Australia, Mount Uluru will be invisible; in Bermuda, you could sunburn and not know it; in Switzerland, the Matterhorn will appear bright pink. Rose-colored glasses are likely rarely abused at the Grand Canyon, where at close of day the sky turns purple, the sun glows orange, and the clouds blush pink.  |

Whimsy aside, although the exact origin of the idiom has been lost in the "rose-coloured mist" of time (Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit, 1856), we can speculate that it may reference the sanguine light of sunset, when the world is momentarily bathed in rosy radiance. That healthy glow is soon followed by twilight blindness and then impenetrable darkness—hence the air of suspicion. Ironically, though, private investigators and varmint hunters assure us that red lenses help the eyes adjust to low lighting and improve one's night vision. That's because red lenses filter out lower wavelengths and reveal a brighter panorama. So the poetic caution against rose-colored glasses would appear to be ill-conceived. Indeed, Dr. John Izzo suggests that figurative rose-colored glasses can be a practical tool enabling starry-eyed romantics to pinpoint their ideals and pursue them with focus. He explains: "Usually meant as an insult, [seeing the world through rose-colored glasses] is a way of saying that someone is a bit too innocent, that he or she sees the world with too much optimism. The intimation is straightforward: Wake up and smell the coffee. Some people see the world through other kinds of glasses—cynical glasses—and surely the lenses they choose color their experiences. When it comes to rediscovering wonder and innocence . . . few decisions are more critical than choosing your glasses" (Second Innocence: Rediscovering Joy and Wonder, p. 73). Dr. Izzo seems to be suggesting that in the absence of adopting some sort of rosy focal point, one is likely to see a world limited to depressing shades of grey. It's true that "the particular glasses we wear reflect how we analyze and interpret what we see" (John Peter Rothe, Undertaking Qualitative Research, p. 137), just as the microscopic lens unlocks a richness of detail. These glasses symbolize what Prof. Jerry Griswold calls "forcible shifts in perspective, techniques for seeing things differently." Prof. Griswold cites The Wizard of Oz, "in which Dorothy and her companions put on green glasses before entering Emerald City, and then marvel at how green everything looks. In Pollyanna, however, the equivalent image is, significantly, not rose-colored glasses, but the prism. When the girl hangs dozens of these in the windows of Mr. Pendleton's house, we see something more than her transformation of his gloomy room into a rainbow-spangled place. We see how she has changed him in her prismatic shifts of perspectives. It is her pointing to a spectrum of possibilities, her reminding him of his freedom to choose, which leads Mr. Pendleton to conclude that Pollyanna is 'the very prism of all'" (Audacious Kids, p. 235).  |

In her book Scraps of Life, the poet Carol Loy Miller offers an intriguing perspective on rose-colored glasses which helps to illuminate Dr. Izzo's point. Miller invites us to imagine the world looking back at us through our rose-colored glasses, reflecting back scenery that has been painted "with the themes and colours we seek" (p. 68). Miller intimates that rose-colored glasses bring definition to the constraints of our world so that we can find our own room for expansion.  |

Rose-colored glasses invite us to make a distinction between illusion and idealism, between nostalgia for a lost Eden and inspiration for a new Utopia. As Prof. Griswold notes, "it is possible to remain innocent without being ignorant." While critics fear donning blinders of false optimism, proponents embrace filtering out defeatist views. People like Carol Loy Miller see rose-colored glasses as a means for new levels of self-awareness and new avenues for transformation. The glasses could be likened to virtual reality goggles, allowing the user to preview a bright world of possibility. Along those lines, one might consider rose-colored glasses the perfect accessory to a set of blueprints. For at the end of the day, the "real world" is only as colorful as we decide to make it—the glow of sunset notwithstanding.

by Malingering by Malingering

by Wonderlane by Wonderlane

by Ms Oddgers by Ms Oddgers

[Read the entire article in my guest blog at ColourLovers.com.]

|

|

"These are not coincidences; somewhere there is a relation that from time to time sparkles through a worn fabric." — W.G. Sebald |

|

|

|

|

|

|

by same sameThe Controversy of Naked Colors"It was color as such, naked color, unabashedly itself, and assertively dominant."—Elizabeth Frank, Esteban Vicente

So-called "naked colors" expose a stark naturalness that many viewers would consider titillating or indiscreet. Naked colors invite the viewer to peek into an intimate range of wavelengths that yield a profoundly sensual impression and uncover a hidden truth. Naked colors embody what the French phenomenological philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty calls "interpenetration," wherein the fine line between a public arena and a private one starts "gaping open" (qtd. in Henry James and the Philosophical Novel, by Merle A. Williams, 1993). In other words, Merleau-Ponty is suggesting that a naked color on a visible surface can serve to lead the imagination toward something typically not visible. Naked colors appear in the art world and the natural world. The red and gold Santa Rita mountains and the violet Catalina mountains of Arizona display a "wild bright beauty" of "naked color" (Glenn Hughes, Broken Lights: A Book of Verse, 1920). In the springtime in London's city parks, flower bulbs "break against the renewing grass in naked colour" (David Piper, The Companion Guide to London, 1983). In the Dutch painter Pieter Mondrian's later work, he focused his attention to "'naked' color dynamics: patches of pure red, yellow and blue held in place by a grid of black lines (Jon Thompson, How to Read a Modern Painting, 2006). In the world of fashion, "naked color turns into decorationism" (Marc Chagall, Marc Chagall on Art and Culture, 2003). However, quantum physicists tell us that "naked colour is never to be seen" in quarks (Nigel Calder, Magic Universe: The Oxford Guide to Modern Science, 2003). [Read the entire article in my guest blog at ColourLovers.com.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by Michele C.Pure Photography: The Black and White of a Fleeting Artistic MovementEstablished in 1932, the Pure Photography movement boasted a palette with a maximum of two colors. Pure photography was defined as being completely free of any other artistic movement. That meant it had to be free of qualities of technique, composition, and objective. Due to its strict requirements, the possible body of work was severely limited. That's why the visual poet Geof Huth calls Pure Photography "one of the shortest artistic movements of all time." As it is such a narrow school of art, Huth was able to complete all the possible works of the genre in a single day. He explains: "A black & white photograph might look like it is made out of grays, but it is made out of bits of black organized on the surface of a white sheet, so in its purest form it is either all black or all white."

Huth's technique was simple: "The black photograph must be exposed to uncontrolled light, so I turned on the lights in the darkroom, exposed the paper & then developed the photograph. The white photograph must never be exposed to light; it is fixed so that it never changes from its white beginnings. I framed one of these photographs in a bright metal frame, but I don't know where it is anymore." [Read the entire article in my guest blog at ColourLovers.com.] Jeff writes: I'd never even heard of the Pure Photography movement, but freedom from the "qualities of technique, composition, and objective" is intriguing, particularly in the context of photography. It just doesn't get much more minimalist — I especially love that strict black and white palette! And in 1932 no less!

I loved this, too: "Due to its strict requirements, the possible body of work was severely limited." Ha!

Thanks for the enlightening (and entertaining) article!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

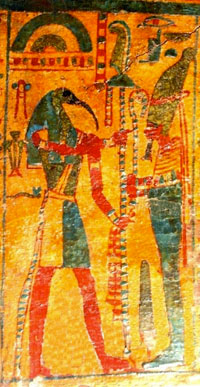

by wispalexAncient ColorsThe roots of color technology trace back to Ancient Egypt, where visionary chemists concocted recipes for synthetic pigments. Color (Ancient Egyptian name 'iwen') was an essential part of life in ancient Egypt, adding deeper meaning to everything the people created. Paintings, clothing, books, jewelry, and architecture were all imbued with colorful symbolism. African historian Alistair Boddy-Evans explains that color "was considered an integral part of an item's or person's nature in Ancient Egypt, and the term could interchangeably mean color, appearance, character, being, or nature. Items with similar color were believed to have similar properties." Egyptologist Anita Stratos informs us that the Egyptian palette had six colors: - red (desher)

- green (wadj)

- blue (khesbedj and irtiu)

- yellow (kenit and khenet)

- black (khem or kem)

- white (shesep and hedj)

Boddy-Evans notes that organic sources yielded two basic colors: crushed bones and ivory provided white pigment, and soot provided black. Red dye was produced from the dried bodies of female scale insects (family Coccidae, genus Kermes). Indigo and crimson pigments came from plants. Most other colors were made from mineral compounds, Stratos notes, "which is why they retained their vibrant colors throughout thousands of years."

Ancient Egyptians considered green to be a positive and powerful color, Egyptologist Geraldine Pinch notes (Magic in Ancient Egypt, 1995). It was associated with fertility, growth and regeneration. "A person was said to be doing 'green things' if his behavior was beneficial or life producing," Stratos says. "Wadj, the word for green, which also meant to flourish or be healthy, was used for the papyrus plant as well as for the green stone malachite. Green malachite was a symbol of joy. In a larger reference, the phrase 'field of malachite' was used when speaking of the land of the blessed dead."

Blue and turquoise were considered divine colors and appropriate for sacred places. Stratos explains that "Dark blue, also called 'Egyptian' blue, was the color of the heavens, water, and the primeval flood, and it represented creation or rebirth. The favorite blue stone was lapis lazuli, or khesbed, which also meant joy or delight. . . . There is also a theory that blue may have been symbolic of the Nile and represented fertility, because of the fertile soils along the Nile that produced crops. Because the god Amen (also spelled Amon or Amun) played a part in the creation of the world, he was sometimes depicted with a blue face; therefore, pharaohs associated with Amen were shown with blue faces also. In general, it was said that the gods had hair made of lapis lazuli."

Stratos explains that red was considered a very powerful color, "symbolizing two extremes: Life and victory as well as anger and fire. Red also represented blood. . . . In its negative context of anger and fire, red was the color of the god Set, who was the personification of evil and the powers of darkness, as well as the god who caused storms. Some images of Set are colored with red skin. In addition, red-haired men as well as animals with reddish hair or skins were thought to be under the influence of Set. A person filled with rage was said to have a red heart."

"In the Graeco-Egyptian papyri, a special kind of red ink, which included ochre and the juice of flaming red poppies, was used," Pinch says. The color yellow "designated the eternal and the indestructible, also considered to be qualities of the sun and of gold," says Stratos. "Many statues of the gods were either made of gold or were gold-plated; in fact, Egyptians believed the gods' skin and bones were made from gold. Tomb paintings showed gods with golden skin, and pharaohs' sarcophagi were made from gold, since the belief was that a deceased pharaoh became a god." Incidentally, the color orange would have been classified as yellow in Ancient Egyptian times.

Sometimes, Stratos notes, yellow was used interchangeably with white. "White denoted purity and omnipotence, and because it had no real color, it represented things sacred and simple. White was especially symbolic in the religious objects and ritual tools used by priests. Many of these were made of white alabaster, including the Apis Bulls' embalming table. 'Memphis,' a holy city, meant 'White Walls,' and white sandals were worn to holy ceremonies. White was also the color used to portray most Egyptian clothing."

Black was a symbol of night, death, and the underworld. Stratos explains: "We see this reflected in Osiris, who was referred to as 'the black one' because he was king of the afterlife, and also with reference to the god of embalming, Anubis, who was portrayed as a black jackal or dog. Because Queen Ahmose-Nefertari was the patroness of the necropolis, she was often shown with black skin." Black also symbolized resurrection, an idea likely related to "the dark silt left behind by the annual Nile flood. From the most ancient Egyptian times, Egypt was known as Kemet, or 'the black land,' because of the dark soil of the Nile Valley; therefore, the color black symbolized Egypt itself. When used to represent resurrection, black and green were interchangeable."

[Read the entire article in my guest blog at ColourLovers.com.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Some uncommon wisdom from unlikely sources: • Never go with a hippie to a second location. ( 30 Rock, NBC series) • Never drink with a savage. ( The Western Lands by William Burroughs) • The best way to avoid a confrontation with a stranger: never walk through a strange neighborhood. ( Maharishi Mahesh Yogi) • Nothing is better calculated to antagonize the wealthy than to ask for a small loan. ( The Western Lands by William Burroughs) • There is no cure for injustice other than committing another injustice to correct the first—let the river wash away the bad blood. ( Ancient Evenings by Norman Mailer) If you've heard uncommon wisdom from unlikely sources, please share!

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Literary rapscallion Jonathan Caws-Elwitt wonders whether one can "like it and lump it":

Merriam-Webster tells me that the transitive verb lump can mean "to group indiscriminately," or "to move noisily and clumsily." Now, the imperative phrase lump it, of course, is usually heard as part of "like it or lump it." But my problem is that I'm not sure how to lump it, if called upon. Am I supposed to group things indiscriminately, if I don't like whatever "it" is? Or move something noisily and clumsily? (Chances are, I'm already doing that, without being asked.)

And why all this mutual exclusivity? Cannot one like it and lump it?

Humorist Jonathan Caws-Elwitt's plays, stories, essays, letters, parodies, wordplay, witticisms and miscellaneous tomfoolery can be found at Monkeys 1, Typewriters 0. Here you'll encounter frivolous, urbane writings about symbolic yams, pigs in bikinis, donut costumes, vacationing pikas, nonexistent movies, cross-continental peppermills, and other compelling subjects.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

by PerlaOctarine: The Imaginary Color of Magic"Octarine" is a color name coined by Terry Pratchett in his Discworld novels. Octarine is said to be the color of magic, as it is apparent in the crackling and shimmering of light. The word refers to the "eighth color," in a spectrum of black, blue, green, yellow, purple, orange, and red. Octarine has been likened to a fluorescent greenish-yellow purple, a combination impossible to perceive with normal human eyes. Imagine, if you can, the marriage of these two swatches:

Scholar of magic Pete Carroll says he imagines Octarine to be "a particular shade of electric pinkish-purple," a common color in optical illusions. Who can see octarine with the naked eye? Legend has it that only wizards and felines can. That's because an ordinary eye, equipped with rods and cones, would see greenish-yellow purple as gray, black, or nothing at all, while a wizard's eye is said to be equipped with octagons. Some people claim to catch glimpses of octarine in peacock feathers, lightning bolts, rainbows, lens flares, soap bubbles, bonfires, and gemstones. There can be no doubt that octarine is an imaginary color. But is it preposterous to think that normal human eyes might one day be able to perceive a fluorescent greenish-yellow purple? The folks at the Conscious Entities blog posed that very question: "There has to be an octarine, doesn't there? The mere conceivability of another color shows that the spectrum is not an absolute reality. It seems to me that, just as we can always encounter a completely new smell, there would always be scope for a new color, if our eyes were able to develop new responses the way our nose presumably can. But I don't even need to rely on conceivability. Some insects can see ultraviolet light, for example, and some snakes can see infrared. They must assign to those wavelengths colors which we can't see, mustn't they?" Their conclusion, however, is negatory: "Look at the way the spectrum forms a closed circle. If we extended it downwards below red, we should simply get another, lower, violet. Now I grant you that the 'lowerness' would have to expressed in some way - possibly as 'warmth.' The colors of the visible spectrum are differentiated in terms of warmth, so perhaps the lower violet would appear distinctly warmer than the one we're used to (great scope for interior decorators...). I repeat, the spectrum is a reality. You can call it a mathematical reality if that helps, but it's real. If we saw color the way we hear pitch, all this would be obvious. But the fact that we can't see color harmonies or more than a single octave of colors means there's never been any scope for a genius to come along and produce a regularised interpretation of the spectrum, the way J.S.Bach did for the musical scale." [Read the entire article in my guest blog at ColourLovers.com.]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

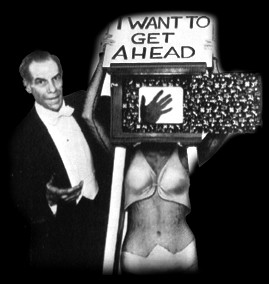

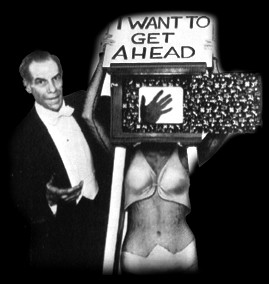

The documentary Women in Boxes, spearheaded by Blaire Baron Larsen, is a springboard for pondering the deeper significance of magicians placing their assistants in boxes. As performers, the duos likely have no idea what archetypal stories they're playing out. But something profound is going on, in light of the renowned psychologist Erich Neumann, a trailblazer in feminine psychology and the Great Mother archetype of world mythology. Applying Neumann's insights to stage magic, the prototypical female assistant symbolizes the anima -- that part of the psyche connected to the world of the subconscious -- the soul, if you will. The anima can be human or animal (hence the great tradition of women magically transforming into tigers). The prototypical male magician symbolizes the hero archetype on a quest toward individuality. In order to be truly creative, the magician's masculine world of ego consciousness must make a link to the feminine assistant's world of the soul. Through "sawing a lady in half," the magician tries to divide the anima, not so much to conquer her but to understand her like a scientist. He tries to contain the anima in a box, not to imprison her but to accommodate, encompass, and give definite form to her curvaceous amorphousness. Indeed, there's nothing inherently "sexist" about the roles of stage magician and assistant; the two form a single personality struggling to become integrated. (Read more of Neumann's wisdom in his indispensable The Origins and History of Consciousness. Here's a link to Camille Paglia's profile of Neumann).

|

|

|

Page 160 of 170

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2025 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|