I Found a Penny Today, So Here’s a Thought

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

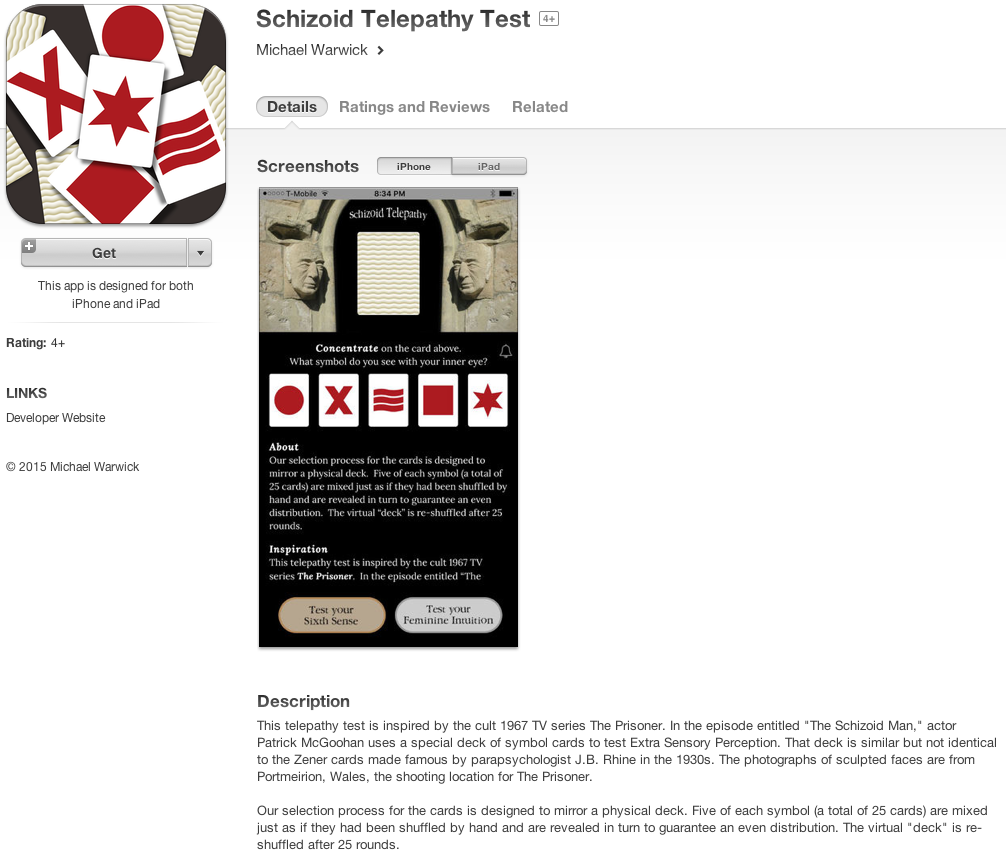

This app is based upon a telepathy test that the Official Prisoner Appreciation Society commissioned us to design back in 2008. In the episode of The Prisoner entitled "The Schizoid Man," actor Patrick McGoohan uses a special deck of symbol cards to test Extra Sensory Perception. That deck is similar but not identical to the Zener cards made famous by parapsychologist J. B. Rhine in the 1930s. We created an exact replica of the prop deck to the delight of the Society, but as fate had it the cards never went into print.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

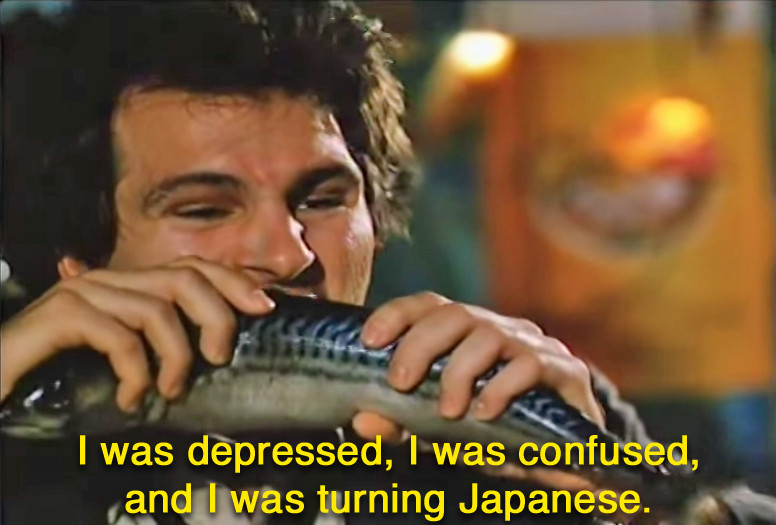

Spin the dial at every crossroad and let Fate lead your journey. This four-tiered oracle suggests which direction to turn and alerts to special circumstances along the way. Try it when wandering a botanical garden for the first time, or if you find yourself lost, or if you wish to lose yourself.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

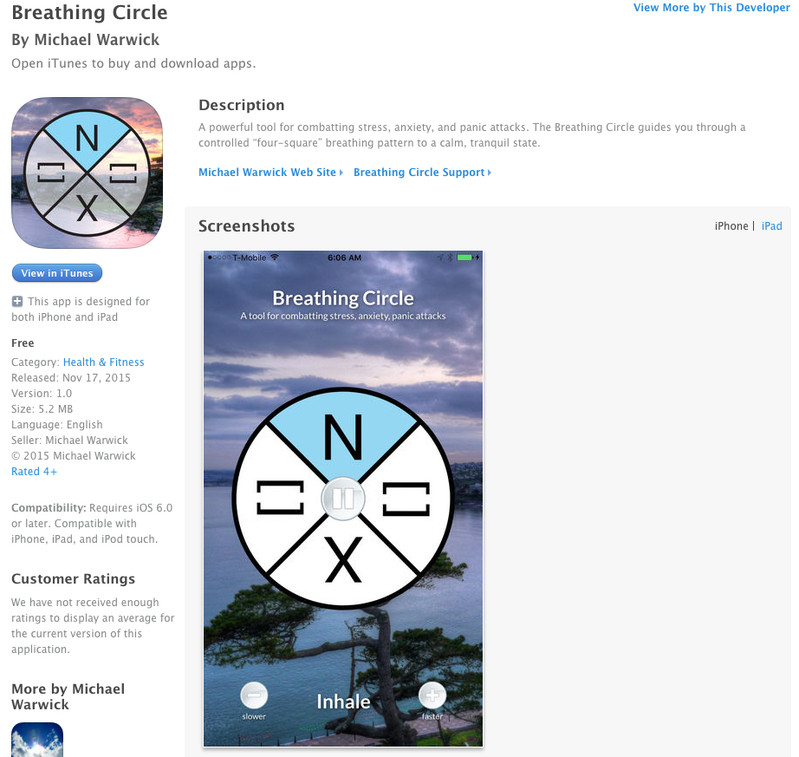

It's a tool for combating stress, anxiety, and panic attacks. We "circled the square" by transforming the technique of four-square breathing into a wheel of life.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

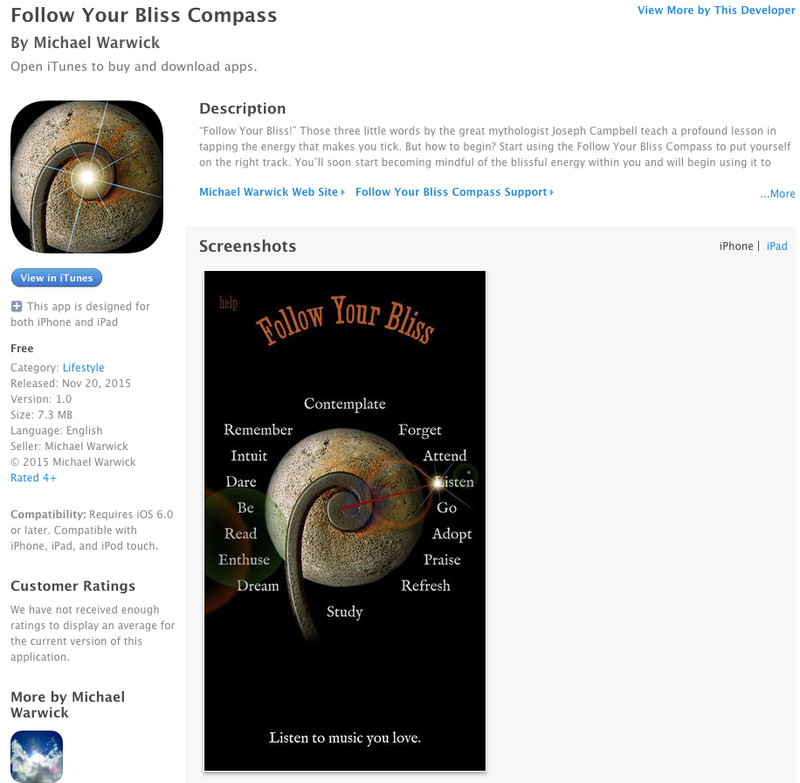

The three little words "follow your bliss," by the great mythologist Joseph Campbell, teach a profound lesson in tapping the energy that makes you tick. But how to begin? Start using the Follow Your Bliss Compass to put yourself on the right track. You'll soon start becoming mindful of the blissful energy within you and will begin using it to make empowering changes in your life. Following your bliss is always a real adventure—a journey into the uncharted center of yourself.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

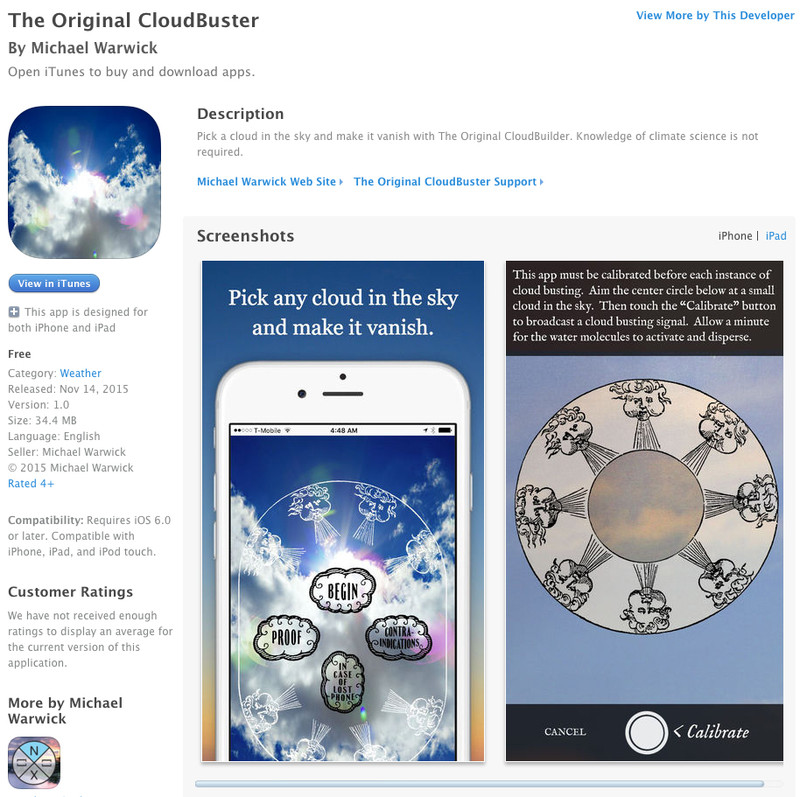

We've been working on this for six years, and it's finally perfected: a Cloud Busting app. No one can predict the weather, but at least now you can control it. They said our blue-sky research wasn't practical, but with this CloudBuster app you can dissolve any clouds you wish and clear the way for a better day. Out of respect to farmers and others who depend upon rainfall, please don't perform cloud busting in drought-prone areas.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

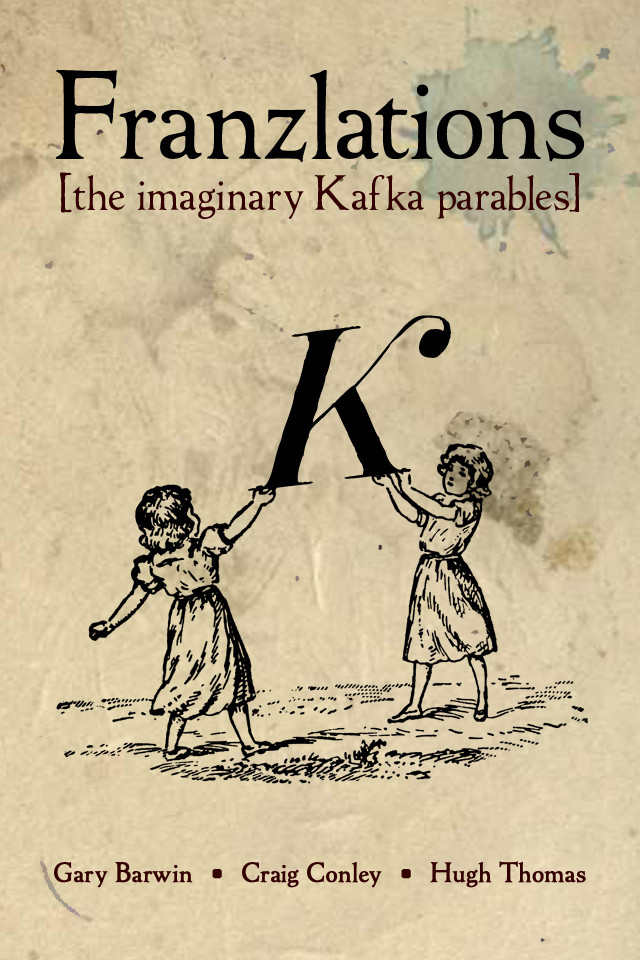

"There are more stories than could be read in a single lifetime. And even if you, dear reader, began reading, by the time you read even a fraction of them, the meanings of the previous stories would have changed. . . . Now all we need to create is more time, more memory, and a few more infinite readers like you."

"Everyone carries a TRAIN about inside of him. Sitting across the table from someone, when all is quiet, sometimes you can hear the whistle blow."

"We were SNAKES. Around us the jungle sighed. A woman offered us fruit. We ate and knew that we were not naked, nor human. She and her companion left. We remained."

"If you were walking across a barren plain and had an honest intention of walking on, then it would be a desperate matter, but you are flying, gliding and diving, SOARING and swooping, high above the plain, which, seen from above, is a tiny blot on a vast and various landscape."

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

We were surprised to encounter the Zen game we invented, Moon Fish Ocean, described in a novel entitled The Woman Who Woke Up In The Zen Forest, by Martin Avery (2010). Perhaps a footnote might be in order for the next edition, Mr. Avery? ;-) Otherwise, glad to see that the game is inspirational!

|

|

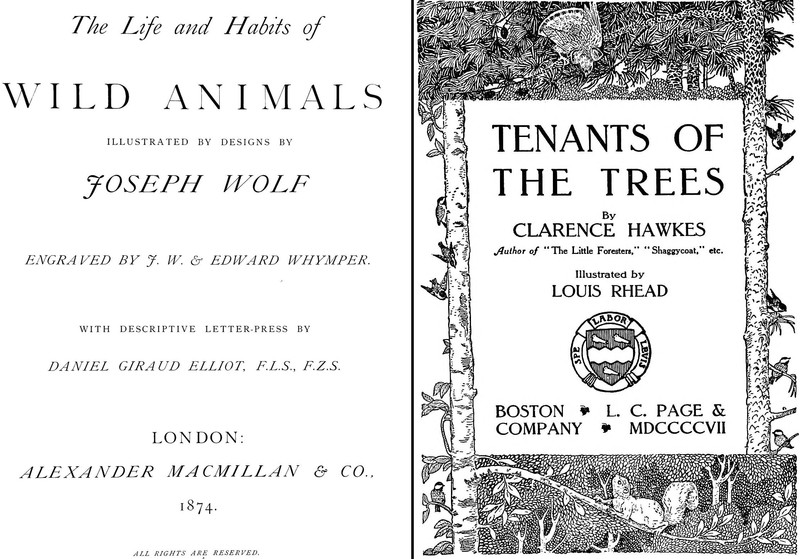

We encountered these books one after the other today — wild animals described by a Wolf alongside Hawkes' tenants of the trees. We've seen enough examples like these to wonder whether a career could possibly be shaped by one's name, as in that meme about how a disproportionate number of dentists are named Dennis. Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry from Forbes tries to bah-humbug the fun by countering the report in the New Republic, saying: "Even if it were true that there were more dentists called Dennis, there would still be no evidence for having the name Dennis causing people to become dentists." Pascal-Emmanuel Gobry doesn't address what exactly caused him to write about probability over a career in dentistry, and we wouldn't dream of mentioning that another fellow named Pascal just so happened to have founded the theory of probabilities.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"Water is almost nothing, after all. It is conspicuously different from air only in its tendency to flood and founder and drown, and even that difference may be relative rather than absolute." —Marilynne Robinson, HousekeepingSimilarly:

|

Page 139 of 171

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2025 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|