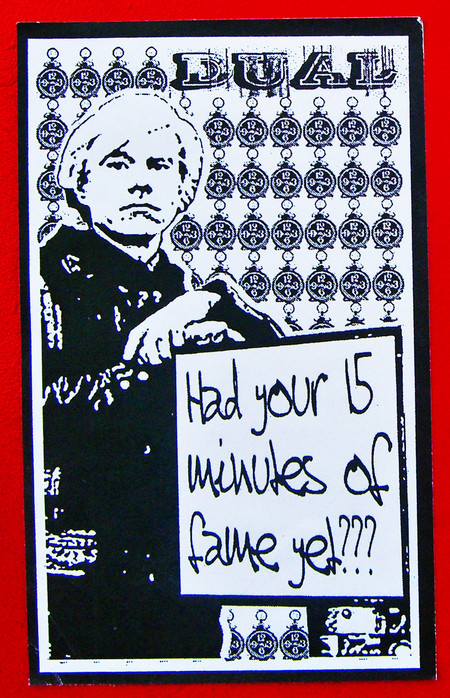

Perhaps Andy Warhol Was Wrong, For a Fascinating Variety of Reasons

[Updated with new wrongness!]

Andy Warhol famously predicted that in the future, everyone would be famous for fifteen minutes. Now that the future is already here, there are those who beg to differ with Andy, and for a fascinating variety of reasons!

In his novel Rant (2007), Chuck Palahniuk suggests that "Andy Warhol was wrong. In the future, people won't be famous for fifteen minutes. No, in the future, everyone will sit next to someone famous for at least fifteen minutes."

Movie critic Frank Schneck posits that the word should be film, not fame: "Andy Warhol was wrong. It's not just that everyone is going to have 15 minutes of fame. In the not-so-distant future, every person on the planet is going to have a film made about him or her" (Hollywood Reporter, 2000). Others seem to agree, in a roundabout way:

"

Andy Warhol was wrong. Today it seems that anyone can parlay their 15 minutes of fame into 15 cable episodes, with an option for a second season."

—"It's Unreal How Easily Reality Shows Pop Up,"

Rocky Mountain Daily News, July 20, 2002

"

Andy Warhol was wrong. Everyone's not going to be famous for 15 minutes; instead, we will all have our own talk shows."

—"Ex-Dancer, Ex-First Son Tries a New Career: Talk Show Host,"

Buffalo News, Aug. 16, 1991

Then there are those who argue that the 15 minutes are recurring:

"The couple who wrote and performed the theme to the 1970s TV series "Happy Days" are on a media blitz in Colorado Springs this weekend, proving that Andy Warhol was wrong. Not only will everyone in the world get 15 minutes of fame, they'll get another 15 minutes when the nostalgia factor kicks in a couple of decades later."

—"These Days Are Happy for Couple," The Gazette, March 6, 1997

"Andy Warhol was wrong ... People don't want 15 minutes of fame in their lifetime. They want it every night."

—"Pseudo's Josh Harris," BusinessWeek, Jan. 26, 2000

"Andy Warhol was wrong. With the release of the film, Factory Girl, he and his 'superstars' are about to get another 15 minutes of fame."

—"Straight to the Point," Daily Mail, Sept. 27, 2006

"As it turns out, Andy Warhol was wrong: not everybody will be famous for 15 minutes. But with bad prospects and a good agent, those who once were can now extend the clock thanks to unprecedented TV demands for the vaguely familiar."

—Vinay Menon, "More Dancing with Quasi-Celebs," Toronto Star, March 19, 2007

Not fame, but Hitler:

"Andy Warhol was wrong. In the future, everyone will be Hitler for 15 minutes."

—"Originality is the First Casualty of War," Austin American-Statesman, April 1, 1999

"Andy Warhol got it wrong. It's not fame everyone will have in the future; It's a chance to scream at someone else on TV."

—"Clinton Vs. Dole About Ratings, Not Discourse," Witicha Eagle, March 11, 2003

Not fame, but privacy:

"Andy Warhol was wrong. The wild-eyed artist boldly proclaimed that in the future everyone would have 15 minutes of fame. Warhol's fortune-telling skills were nowhere as visionary as his art. Warhol should have predicted with the explosion of reality television that in the future everyone will have 15 minutes of privacy."

—"One Day, We'll Beg for Privacy," Fresno Bee, Aug. 3, 2000

Not fame, but Colorado citizenship:

"Andy Warhol was wrong. It turned out we were all from Colorado."

—Barry Fagin, "Montel Williams and Me," Independence Institute, Nov. 1, 2000

Not fame, but hostage crisis:

"In the future, everyone will be a hostage for fifteen minutes." —William Keckler

Fame, yes, but in the past, not in the future:

"Andy Warhol was wrong. Everybody already has been famous––some time last week. It just depends on who’s telling it and who’s listening."

—"The Remembering Game," Depot Town Rag, Sept. 1990

Fame, yes, but not 15 minutes exactly:

"The culture-shock doctor explained that science had discovered that Andy Warhol was wrong about fame; He had the right idea, but his figures were off."

—"The Sting of Cable Backlash," Miami Herald, Oct. 9, 1983

"'Andy Warhol was wrong,' Neal Gabler said. 'He was right when he said everyone will be famous, but wrong about the 15 minutes.'"

—Marjorie Kaufman, "Seeking the Roots of a Celebrity Society," New York Times, Dec. 11, 1994

"Andy Warhol got it wrong by 12 minutes. People have three minutes of fame; long enough to walk down a catwalk and back."

—Guardian, July 7, 2002

"Warhol was wrong ... cos he was 10 minutes off; it's really five minutes now."

—"Meat Loaf Criticises Academic 'Laziness,'" TVNZ, March 9, 2010

Fame, yes, but for more like 15 seconds:

"Andy Warhol was wrong. Everyone can be famous these days, all right, but the renown lasts more like 15 seconds, not minutes."

—"Smile! You're Part of a Video Society," Greensboro News and Record, May 20, 1990

"Andy Warhol was wrong when he said that everyone would have 15 minutes of fame; extras can look forward to having only seconds of movie glory."

—"12 Hours' Extra Work for a Brief Moment of Glory," Derby Evening Telegraph, Nov. 9, 2006

"[A cuckoo clock bird speaking:] Andy Warhol was wrong; I only get 15 seconds of fame."

—Mike Peters, "Mother Goose and Grimm," July 27, 2005

"Andy Warhol was wrong. In my case, at least, fame clocked in at only 6:42 minutes, and that was before the final cut."

—Wilborn Hampton Lead, "Confessions of a Soap Opera Extra," New York Times, Dec. 31, 1989

"Andy Warhol was wrong when he said that everyone will enjoy their fifteen minutes of fame. The time frame he referred to might one day be measured in seconds."

—Warren Adler, "The Dividing Line," Aug. 10, 2009

"

Little did I realize that not only would there be no money, but that your star would flicker for two seconds and that was it." —Holly Woodlawn, quoted in her NY Times obituary, Dec. 7, 2015Fame, yes, but for more than 15 minutes:

"Andy Warhol was wrong. You can be famous for a lot longer than 15 minutes, if you're clever enough."

—"Oliver's Brand of Revitalisation,"

Marketing Week, April 7, 2005

"'We were sure that Andy Warhol was wrong, that it would last more than 15 minutes,' says Hilary Jay.'"

—"Maximal Art and Its Rise from the Ashes,"

Philadelphia Inquirer, July 25, 1993

"When it comes to the Super Bowl, Andy Warhol was wrong. Its cast of characters has been famous for 25 years, and will be 25 years from now."

—"Simply the Best,"

Denver Post, Jan. 27, 1991

"Andy Warhol was wrong. Long after the buzzer sounded on Mark Fuhrman's 15 minutes of fame, he just won't go away."

—"Fuhrman Overstaying His Welcome," June 10, 2001

"Andy Warhol was wrong: sometimes you do get more than 15 minutes of fame, even if you're not Greg Louganis."

—

National Review, Dec. 10, 2004

"Andy Warhol was wrong. Not everyone gets 15 minutes of fame. Many people get more than that. Like Dr. Bernie Dahl."

—

The Nashua Telegraph, Dec. 3, 2000

"Andy Warhol was wrong. In the Ultimate universe we’ve got more than 15 minutes."

—"Hack Meets Hacker,"

Aspen Magazine, Midsummer 1996

"Andy Warhol was wrong … you can have 45 minutes of fame, not just 15!"

—"Invitation to Present at the OTM SIG Conference in June 2009," Dec. 22, 2008

"Andy Warhol was wrong in my case; my fifteen minutes of fame have been more like three hours."

—

Ken Eichele, My Best Day in Golf: Celebrity Stories of the Game They Love, 2003

"Andy Warhol was wrong; I was a hero for at least fifteen hours."

—Gene GeRue, "Tomato Madness," Dec. 17, 2006

"Andy Warhol was wrong. People aren't famous for fifteen minutes; they're famous forever."

—

Arthur Black, Black & White and Read All Over, 2004

Fame, yes, but "in" 15 minutes, not "for" 15 minutes:

"Andy Warhol was wrong, when he predicted that in the future, people would become famous for 15 minutes. This is the future. Now people become famous in 15 minutes. Take Duran Duran."

—Ethlie Ann Vare, "New Echoes of Duran Duran," New York Times, Nov. 24, 1985

Fame, yes, but without measure:

"Andy Warhol was wrong. In the future, everyone will not be famous for 15 minutes. Everyone will just be famous."

—"Cooking Up Celebrity Storm," Boston Globe, Jan. 21, 2000

"Andy Warhol was wrong. No one Is famous for just 15 minutes. These days you get to be famous whenever you feel like it. Just like everyone else."

—"Now, Everyone is Famous! Who Knew?" Associated Press, July 16, 1999

"'Andy Warhol was wrong,' says Newman, who completed his trek in 1987. 'If I wanted to be boring, I could live on this for the rest of my life."

—"Book Lists Sometime-Dubious Firsts," Dallas Morning News, July 31, 1988

"Andy Warhol was wrong about one thing: His own 'fifteen minutes of fame' have never ended."

—Barnes & Noble, review of Andy Warhol Treasures, 2009

"In the internet age, bad headlines no longer go away and Andy Warhol was wrong about his fifteen minutes of fame. If you are infamous now, you are infamous forever."

—Peter Walsh, "Curtis Warren: the Celebrity Drug Baron," Telegraph, Oct. 7, 2009

The opposite of fame:

"Milwaukee futurist David Zach says Andy Warhol was wrong: We aren't going to get that 15 minutes of fame after all. 'It's just the opposite,' Zach says."

—Tim Nelson, "The Skinny," St. Paul Pioneer Press, Aug. 27, 1998

"I think Andy Warhol got it wrong: in the future, so many people are going to become famous that one day everybody will end up being anonymous for 15 minutes."

—Shepard Fairey, Swindle #8, 2006

"Andy Warhol was wrong. Most of us will never come close to being famous—even for 15 minutes."

—"Stepping into the Spotlight," Wall Street Journal, Nov. 8, 1999

Fifteen, yes, but not minutes:

"Andy Warhol was wrong: not everyone deserves 15 minutes of fame. Some people deserve 160 words of recognition ..."

—"Unsung Heroes," What Magazine, Jan. 1, 2004

"Andy Warhol was wrong: for 15 minutes, everybody gets to be a starting quarterback for The Saints."

—"Tyson Still Has Issues," Atlanta Journal, Oct. 16, 1998

"Andy Warhol was wrong: in the future, everyone won't be famous for 15 minutes, but everyone will have their own Web site."

—"Book Review: The Non-Designer's Web Book," Information Management Journal, July 1, 1999

"Andy Warhol was wrong. We've all had our 15 minutes, now we all want a mini-series!"

—"Boy First Believed On Runaway Balloon Found After Frantic Search," New York Post, Oct. 16, 2009

"Andy Warhol was wrong. Everyone won't just have 15 minutes of fame. One day—soon, I suspect—we all will have our very own talk shows."

—Linda L.S. Schulte, "Word's Worth," Baltimore Sun, Jan. 31, 1996

"In the future, we'll all have 15 minutes of future."

—Nein Quarterly

"In the future, everyone will be offended for 15 years."

—Sean Tejaratchi

Fame, yes, but perhaps 30 minutes:

"There are times in life when you just hope that Andy Warhol was wrong and that a merciful God will grant you a second 15 minutes of fame."

—"Confessions of an Embarrassed Viagra Expert," University Wire, Sept. 24, 1998

Just plain wrong:

"The endless parade of disposable rock bands, special-effects movies, potboiler thriller novels and TV sitcoms makes me think that Andy Warhol was wrong."

—"Longtime Newsweek Art Critic Peter Plagens is Also a Painter," Newsweek, April 25, 2002

"A TV producer played by Joe Mantegna muses that Andy Warhol was wrong about everybody being famous for 15 minutes."

—"Allen's 'Celebrity' Witty, Wicked But Shallow," Wichita Eagle, Dec. 9, 1998

"Andy Warhol was wrong - everyone does NOT have their 15 minutes of fame and the overwhelming majority of You're a Star hopefuls would have told him that."

—"The Fame Game's Just Not Worth It," The Mirror, Aug. 25, 2006

"Andy Warhol was wrong. When you’re a Vanderbilt running back, you’re not famous for 15 minutes."

—Anthony Lane, Nashville City Paper, Nov. 5, 2004

"My main conclusion: Andy Warhol was wrong—we won't all get 15 minutes of fame."

—"Using the Internet to Examine Patterns of Foreign Coverage," Nieman Reports, Sept. 22, 2004

"Warhol was wrong! He neglected to factor in the 15 minutes of one's own alter-egos."

—"Warhol was Wrong," GenderFun.com, May 29, 2009

"Warhol was wrong. The message is clear: we do not want your 15 minutes of fame, you can shove it."

—Alix Sharkey, "Saturday Night: The Techno Ice-Cream Van is on its Way," The Independent, June 26, 1993

---

Stefan writes:

Awesome post on Warhol. I never really liked the guy and his art, but I give credit where credit is due, he was a great coordinator and inspiration for other better artists and musicians. Much like Sex Pistols, I don’t find them good but they did inspire much better bands to get together and create wonderful albums. So I agree he was wrong however he didn’t anticipate the connectivity and subcultural activity we have today which shatters his definition and value of fame. Also nowadays with youtube clips and Jersey Shores fame and infamy seem to be interchangeable. But what I liked about the article was how Warhol’s idea was refuted from different perspectives. Here’s mine: "Warhol was wrong about his theory on the 15 minutes of fame. The time frame is the maximum length of a video you can post on YouTube.” Mine is of course valid for today, just like Warhol’s and those quoted in your post are valid in their own cultural Zeitgeists.