|

|

|

|

|

|

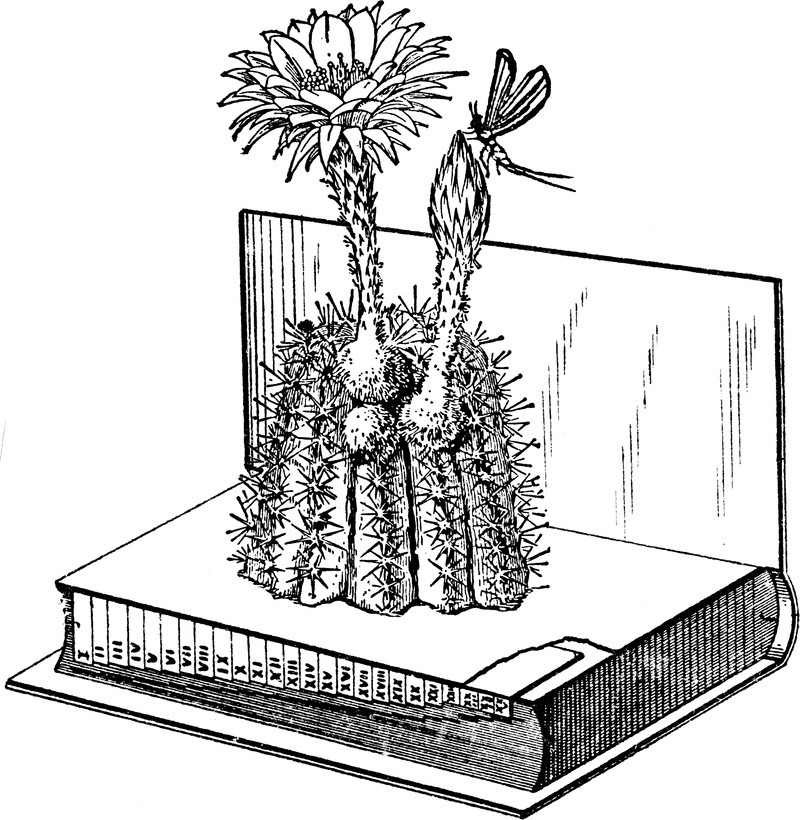

The enjoyably surreal experience of reading a book that is in process of being a cactus

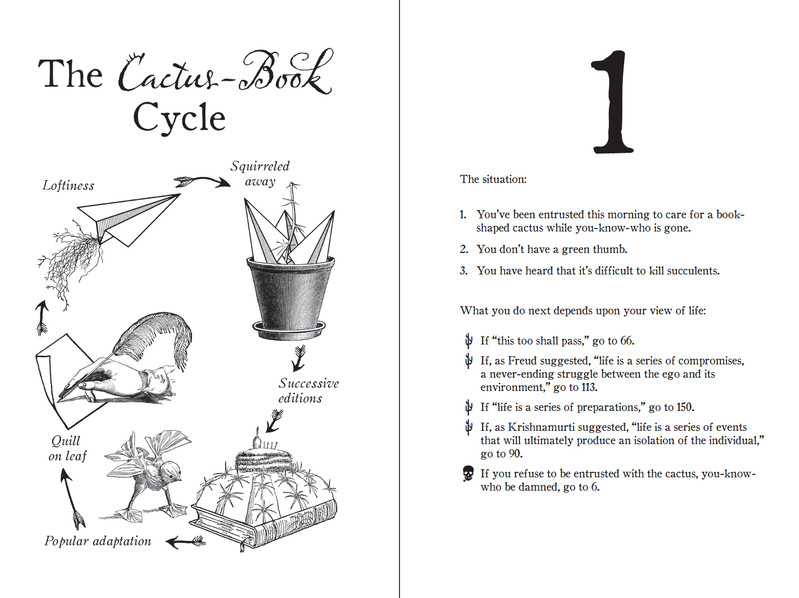

This Book is a Cactus is something quite unique. A friend recommended it to me, and as I have coworkers that I enjoy discussing interesting books and puzzles with, I picked up a copy and did not regret it.For those wondering about the format of the book, since the description mentions a 'virtual game board', the most similar concept (familiar to most people who grew up in the US after the 1970s) would be a 'choose your own adventure' book with more puzzles (not the content, only as a format reference).Initially, my interest in the book was in the overall concept and the puzzles, but quickly I found myself drawn to the prose. It may be a matter of personal taste, but from my perspective the writing and pacing of this book is brilliant. For something that is broken up by decision trees and puzzles, the vignettes and more narrative text joining things together flow incredibly well, but strangely work well as discrete passages. It’s fairly difficult to describe, but it can work as a semi-long form experience, and also as series of short entries (similar to a chapbook of poems) that although are not always dependently connected to the next section of text, did keep propelling me forward. I would read a few (more than I had planned to) ‘pages’ or ‘make a few decisions’ each night before sleep and it would put a healthy amount of strangeness into my subconscious.As a game, I’m not convinced that there is much ‘replay’ value in the book after you have encountered each of the pages or puzzles in a few different orders. As a mix of narrative and puzzles, replay value is largely irrelevant for the genre. As a work of art, ‘This Book is a Cactus’ is a real achievement. Aesthetically, this needs to be a physical book and the excellent illustrations accompanying the text fit perfectly. Conley’s writing has a unique tone that can mix warm humor, surrealism, literate references, with a touch of gray metaphysical and esoteric mystery. If I can employ a less-literary comparison, the feeling I was struck with when reading much of this book, was similar to viewing the first scene in episode 8 of Twin Peaks. It doesn’t shift into the wacky or caustic styles of some other texts dealing with the esoteric. ‘This Book is a Cactus’ employs a calm wit, for a warm mystery, in a foggy, endless bookshelf that might be a greenhouse or more.I foresee and predict that after finishing each page that I will, every now and then, down the road, spot this book on my shelf and pick it up and explore again. By ‘explore’, I mean to give my cactus life.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

"What an intriguing, fun, lovely book with Oddfellow's usual quirky, oblique poetic, metaphysic dry humour and bibliophillic joie de livre. " —Gary Barwin, author of Yiddish for Pirates

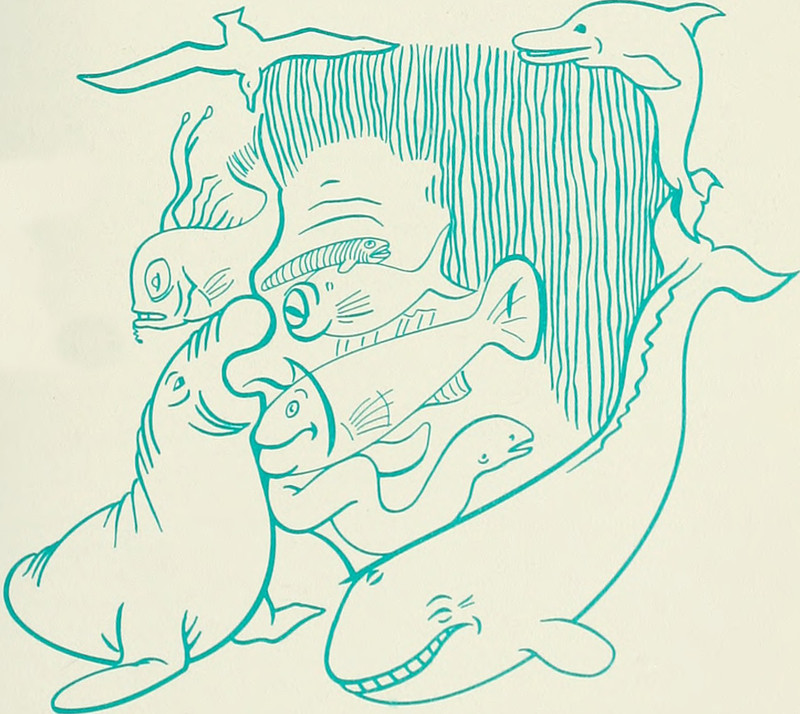

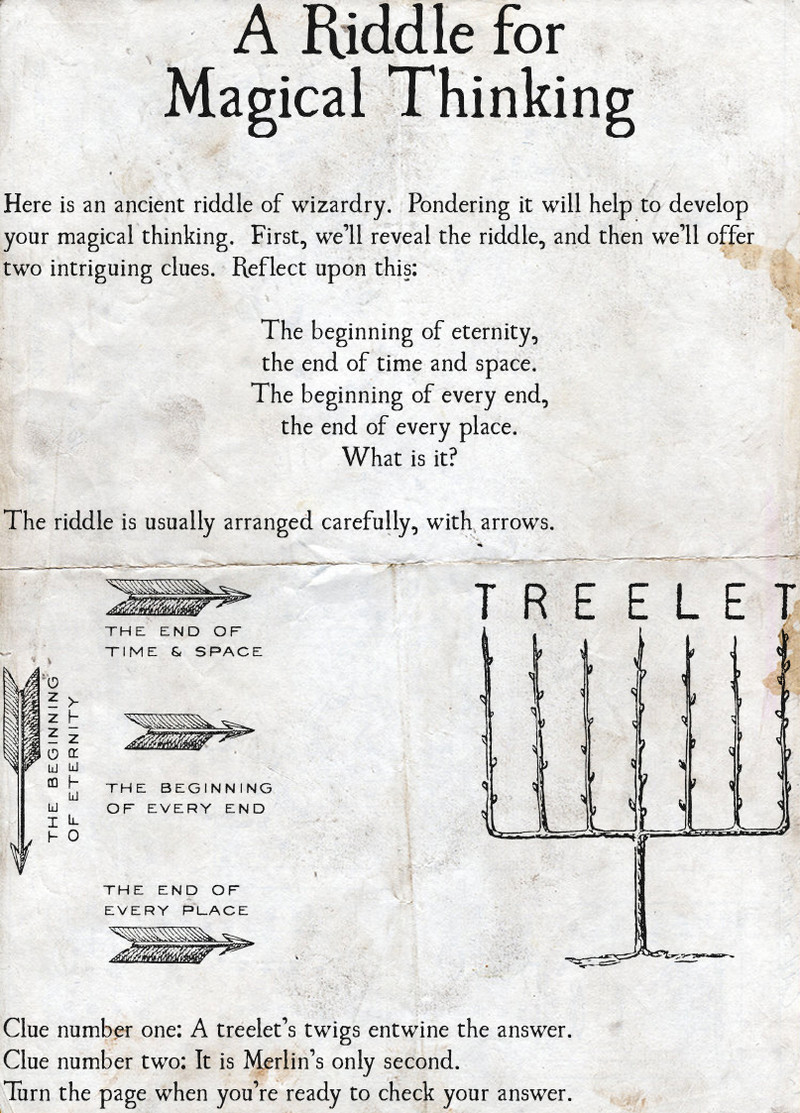

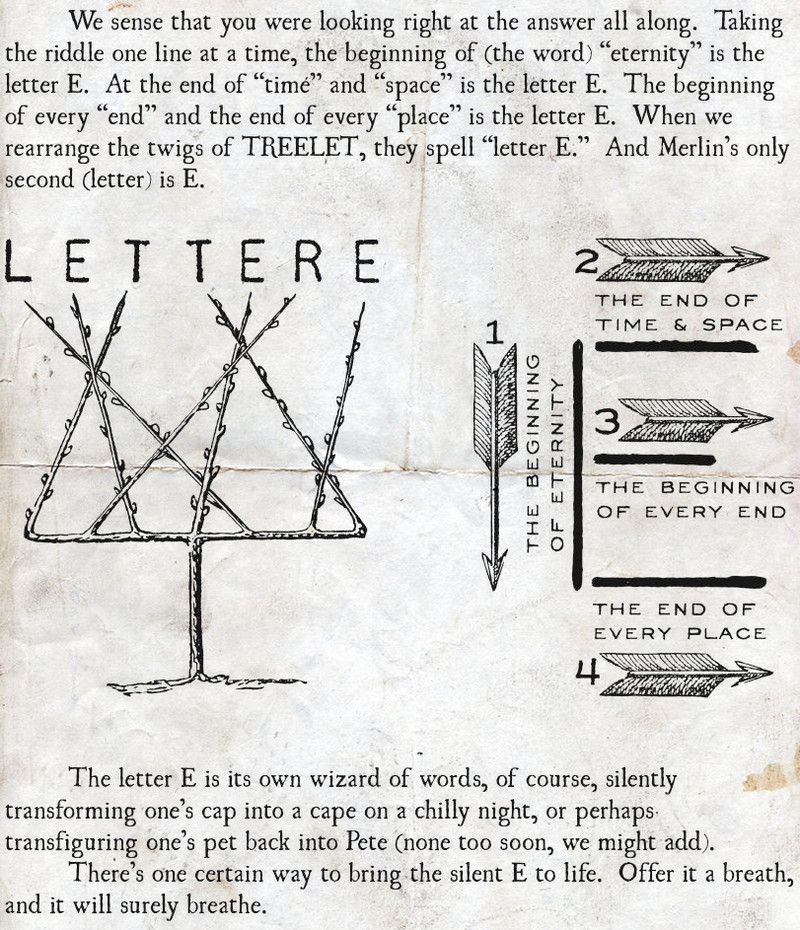

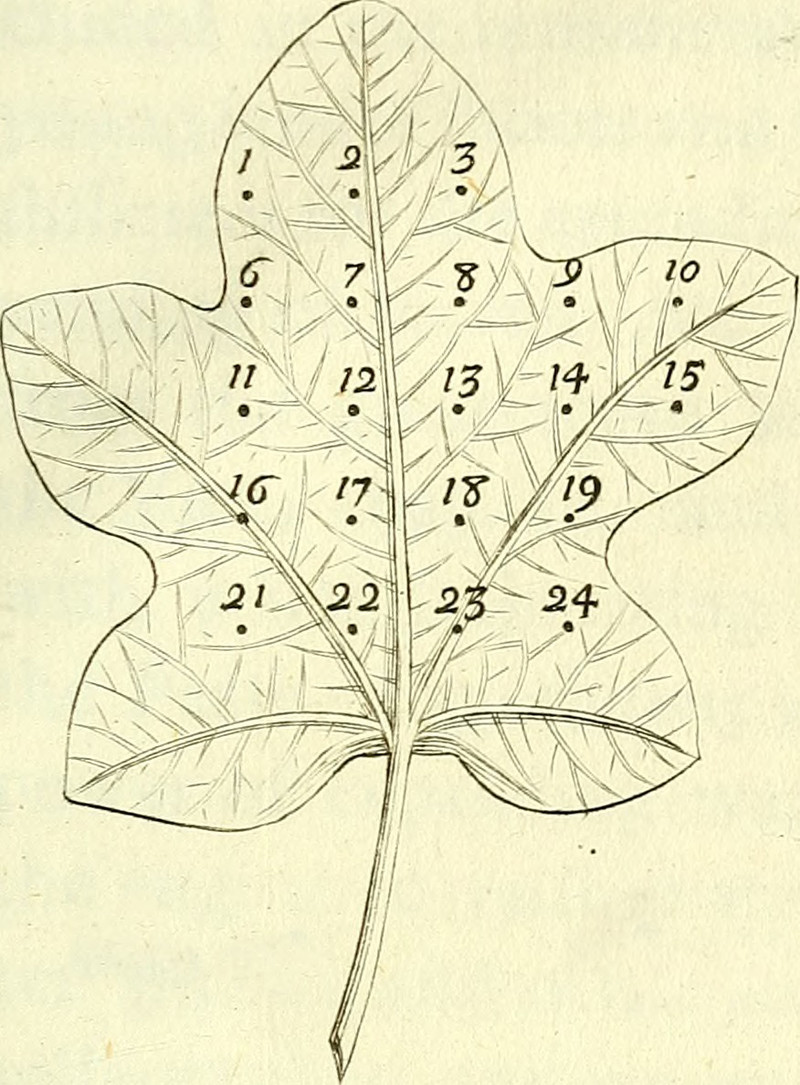

This Book is a Cactus turned out to be the most difficult project we've ever tackled. We wanted to recreate the very first computer game we programmed, from back in the 1980s—the Tamagotchi precursor of a virtual flower—but this time in book form. What we ended up with is a combination choose-your-own-adventure and puzzle book; it's a surrealistic virtual reality experience you hold in your hands, as the book is also a cactus that you attempt to keep alive. A hybrid cactus-book. Each page is like a square on a game board. You make decisions and solve riddles, and your choices/answers lead to different squares. Math puzzles, word puzzles, logic puzzles, and riddles appear at intervals within the fractal storyline.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

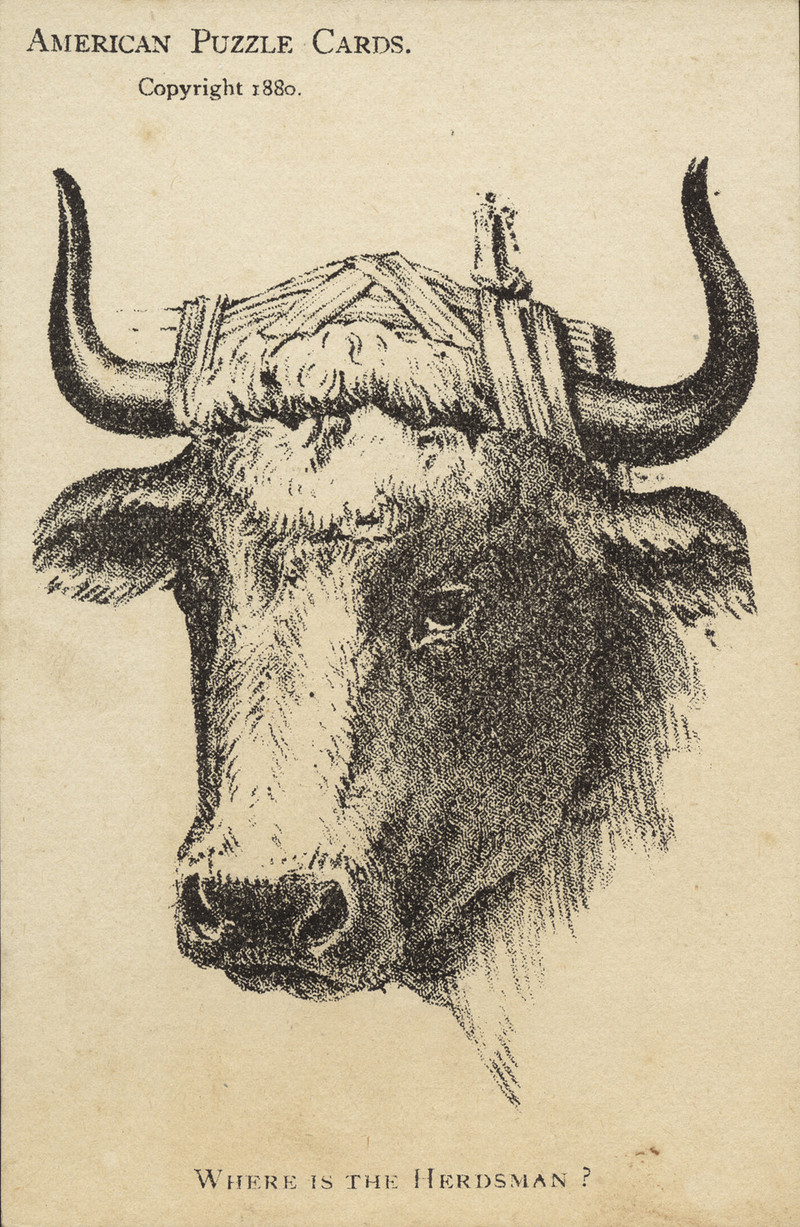

A Facebook session or a Spiritualist seance? Can you tell the difference?

One wishes to make contact with a distant friend, lover, or acquaintance who has departed from one's life. Via means one doesn't fully understand, one seeks a message, albeit oddly spelled or worded, or at least some sort of flickering notification that said entity possesses at least a modicum of sentience in that other place.

a: Spiritualist seance

b: Facebook

c: indistinguishable

[Hint: the answer, like the ocean of consciousness we seek to navigate and commune with, rhymes with the sea.]

|

Page 26 of 29

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2026 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|