|

|

|

|

|

|

Fun with quotation marks: Capital "A" and "Capital A" mean two different things in the context of this old architecture diagram. To learn the surprising answer, see my guest blog at the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Referring to the Dictionary of All-Consonant Words, Jonathan wrote: I visited Merriam-Webster online just now. Due to browser sluggishness, the consonants in the phonetic display of "bookkeeper" loaded first (presumably because the vowels, which are all represented with accent marks, are special characters). For just an instant, M-W was an all-consonant dictionary! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

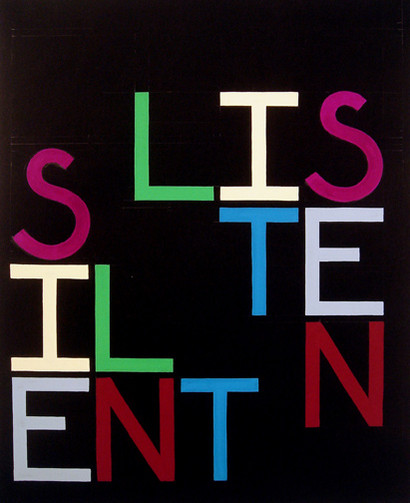

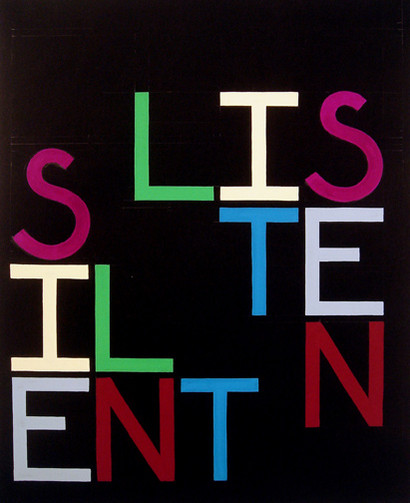

Tauba Auerbach's "Listen/Silent" anagram reminds me of a poem by Thomas Moore: When to sad Music silent you listen,

And tears on those eyelids tremble like dew,

Oh, then there dwells in those eyes as they glisten

A sweet holy charm that mirth never knew.

I like the idea of teardrops being a magical potion, glistening with enchantment of a shadowy (mirthless) yet sacred nature.

This anagram is by Tauba Auerbach and appears here by special arrangement.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

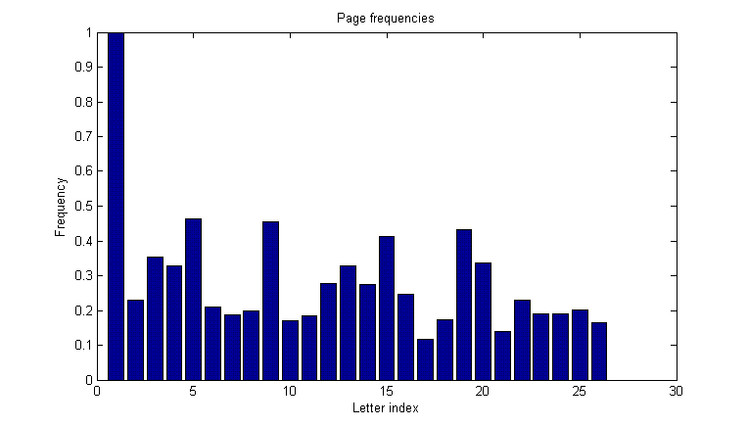

An engineer and armchair philosopher named Joel created this terrific bar graph of one-letter words that appear in Google's 8-trillion page index. "A" is the most common single letter on Google, followed by "e," "i," "o," and "s." At first I was surprised that "v" appears more often than the vowel "u," but then I figured it must have to do with "v" appearing as a Roman numeral. I like how the letter index goes all the way to 30, as if there are slots available for letters that only appear in leap years or something. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

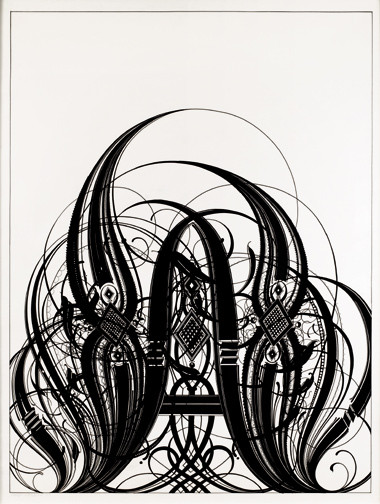

This is my all-time favorite quotation about one-letter words, probably because it encapsulates the concept of the microcosm: I was the only adult in the world who knew that ... a single letter of the alphabet would suffice for the entire encyclopedia. —Sandi Kahn Shelton, Sleeping Through the Night and Other Lies

The illustration of the letter "I" is by Tauba Auerbach, whose alphanumeric work is endlessly fascinating.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

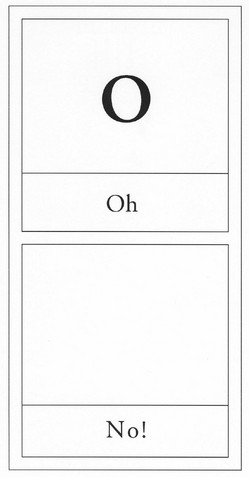

This is from Geof Huth's delightful "Analphabet" project. See the full sized image here, and see the entire collection here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Did you see this Slate headline? What exactly is the dirty word in question? Whence the !@#$?

How a dirty word gets that way.

The headline has a couple of problems. Leaving out the colon between heading and subheading I can understand for clarity purposes [comedy drum roll]. But there's clearly a typo in the third word. Dirty words spelled with random symbols are simply nonsensical. My understanding is that letter substitutions were originally made carefully, not randomly. "Shit," for example, would have been written with a dollar sign for the "s", a pound sign for the "h," an exclamation mark or inverted exclamation mark for the dotted "i", and a dagger for the "t."

$#¡†

Such code is technically meaningless but clearly readable for content. Somewhere along the way, readers apparently weren't clever enough to decipher the obvious code and assumed that dirty words were to be represented by random symbols. And today even Slate boldly perpetuates the error, in bold type no less.

Granted, perhaps Slate meant to coin a new dirty word pronounced "IAHS." I'm game enough to try it out on occasion. Or perhaps Slate has something against the International Association of Hydrological Sciences, or the Institute of Applied Human Services, or even Indo-American Hybrid Seeds.

But that would be horseshit of an entirely different color.

---

Jonathan Caws-Elwitt wrote: Prior to the digital age, it was not uncommon for a typesetter to stumble and upset an entire drawer of metal type onto the floor. The stream of colorful language that escaped the typesetter's mouth at such a moment came to be represented, in print-shop legend, by the chaotic heap of type at the clumsy individual's feet. This may be the origin of the notion that profanity is best represented by a random assortment of characters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inspired by Murray Suid's brilliant and humorous Words of a Feather, I went in search of the origin of flimflam and stumbled upon something more along the lines of a creation myth: A flimflam flopped from a fillamaloo.

—Eugene Field, "The Fate of the Flimflam," Poems of Childhood (1894)

--- Murray responds: Now I've spent a good chunk of my morning looking for a picture of a "fillamaloo" or even a simple definition. Nothing comes up on the Internet. What am I supposed to do--imagine it! Robert D Strock writes: As a youngster, (I am now 85 years old), an old-timer described a "fillamaloo bird" as a native of Panama. Its right leg was longer than its left, so it was a hill dweller that always walked clockwise around the hills. It could fly upside down and backwards, and did so in ever decreasing circles until it flew up its rear end. It then would scream "fillamaloo", which translates as, "Gee, it's dark in here." He didn't have a picture of the creature. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here's a Guest Blog by linguistic riddler Murray Suid, author of Words of a Feather: One of the best things about studying our linguistic environment is accessibility. Unlike Mars or the ocean floor, language is right here. If you have good observation skills, patience, a little imagination, and a dictionary, you can collect many surprising facts. An example is Craig Conley’s discovery that there are 70 meanings for the word “X.” Having been long acquainted with X, I’d have guessed that it had only two or three definitions. I made a similarly gross underestimate when I first observed word pairs that have widely different meanings but close etymological ties. I’m talking about items such as “rectitude & rectum” (both from the Latin “rectus” meaning “straight”) and “denouement & noose” (from the Latin “nodus” meaning “knot.”) In reality, doublets are extremely common. Like a botanist gathering “new” species, I’ve collected doublets for many years. My method is firmly rooted in guesswork. When I see two words that appear to share a linguistic structure, I check out their lineage. Often I’m fooled. For example, this week I speculated–and hoped—that “dupe” and “dope” were relatives. But, alas, they’re not. Fortunately, over the years I found enough amusing pairs to fill the pages of a book: WORDS OF A FEATHER. You can find samples at www.wordsofafeather.net, plus an invitation to submit your own doublet discoveries. Usually, one partner in a doublet is spelled quite differently from the other, for example, “menu & minute” and “senate & senile.” In some cases, only two letters separate the words, for example “mall & mallet” and “hero & heroin.” But inspired by Craig’s research into the meaningfulness of single letters, I wondered: Can we find doublets that differ by just one letter? The answer is “Yes.” For example, “proud & prude” both trace to the Latin “prodesse,” “to be useful.” Here are a few others: * acme & acne * blog & log * pasta & paste * taxis & taxes * thank & think After confirming the existence one-letter-different doublets, I began searching for other words where a single letter plays a significant role. This led me to reduplication, the process of forming a new word repeating the sound an earlier word. Examples include: hanky-panky, mumbo-jumbo, pitter-patter, razzle-dazzle, and walkie-talkie. The investigation of one-letter words doesn’t stop here. But I will. Thanks, Murray, for sharing your fascinating research! _______ Jonathan wrote: I'm wondering if anyone present has insights into the frequent use of reduplication in magic words. --- Craig responded: As I discuss in Magic Words: A Dictionary, phrases like "mumbo jumbo" or "hocus pocus" conjure a mastery over the power to change one nature or form into another. In "hocus pocus," for example, the words actually constitute a formula: A→B, meaning that the substance of A (represented by the name Hocus) transmutes into the substance of B (now Pocus). The formula is a distillation of the intention: “May that which we call Hocus be changed into Pocus.” This distillation, "Hocus Pocus," thereby epitomizes the act of transmutation itself. One can easily imagine a Medieval alchemist, huddled over his instruments, muttering such a formula to himself, as "Hocus Pocus" would be the equivalent to "Lead Gold" ("[May this base metal] Lead [transform into purest] Gold"). --- Murray responded: Jonathan, Thanks for the question...and for leading things off. Craig, I don't have Magic Words...yet. I will today. But I wonder: Are there any reduplicative formulas that turn pedestrian writing into art, for example "prosy rosy"? I ask because after spending most of my writing career on nonfiction, I'm working on a novel. Bland (leady) prose won't do it. By the way, Anatoly Liberman's magnificent WORD ORIGINS...AND HOW WE KNOW THEM has a fascinating chapter on reduplication. If I could write a novel as interesting as Liberman's book, I'd be up there with J. K. Rowling. --- Elizabeth [lizbar AT svn.net] said: The wonderful thing about word play, word tricks, word patterns, is playful insight without heady abstraction. So it is great for kids, for expanding minds, imaginations, possibilities. The youngest can appreciate the sound and rhythm while older children can push boundaries and experiment with the meanings of WORDS. --- Scott wrote: This is a wonderful conversation...thank you for helping shed some light on these wonderful word usages. After all, without words, where would we be? Grunting at each other, possibly with the same level of (mis)understanding, but certainly stripped of the pleasure language gives us. --- Michael wrote: to add further confusion: I'd suggest that magic words is redundant. seeing some as magic and others not presumes a distinction between denotative and connotative meaning. A good case can be made that connotative meaning is all we have, or, the notion of a non-abstract word (or utterance) is mythic (magical?). So what is meaning? well, now we get into it, don't we. meaning can be seen as a negociated understanding or agreement between two speakers (or the writer and reader). Notice that the understanding changes as the process continues. Notice also that meaning changes internally, i.e., is continuously negociated by each of us. Flux, or change, is all we have; the constant is the process. Finally, the human linguistic process is infinitely regressive; it seems that only humans can have a conversation about a conversation about a conversation. We are the only critters we know of with the capactiy of constructing alternative realites not subject to verifiable examination. It is only we who can be schizophrenic. Re Lizbar's comment about word play, Thai kids (Thai being a tonal language) start punning by age 5. It's easy since music (to each sylable) detrminines meaning, or as a linguistic would say, tone is phonemic. --- Craig responds: If intoned in the proper spirit, any word can be a magic word. In The Re-enchantment of Everyday Life (1997), Thomas Moore notes that “we may evoke the magic in words by their placement, . . . rhyme, assonance, intonation, emphasis, and, as [mythologist James] Hillman suggests, historical context.” I distinguish "magic words" in particular as those time-tested, awe-inspiring, poetic utterances spoken with a special reverence for mystique—those enigmatic words and phrases, not usually employed in everyday discourse or conversation, which invoke the powers of creation and destruction when something is to appear out of thin air or to disappear back into the great void. Too often dismissed as “meaningless gibberish,” such magic words are, on the contrary, rich in meaning for those initiated into their significance. And unlike computer-generated gibberish, for example—which typically prompts nothing deeper than shoulder-shrugging or hair-tearing—the sacred vocabulary of mystery-makers has always affected listeners in profound (if indescribable) ways. --- Mike [mwarwick AT pobox.com] responds: I certainly agree that the meaning of every word transforms in parlance. A perfect example is "gay," which once meant "happy," then commonly "homosexual," and now arguably something else entirely. Nevertheless, it strikes me that the bulk of this process of "negotiating meaning" in any particular conversation is to a large extent nonverbal — a fait accompli. Words do bring most of their meaning with them. So perhaps it is not so safe to throw denotation out with the bathwater. I find that Murray's research shows us that if we simply start with an intention to connect a pair of words which look and sound similar (e.g. "dupe" and "dope"), we are hard-pressed to do so because of the divergence of the meanings (and further etymology) that they bring to the table. --- Julie [Casselfamily4 AT yahoo.com] wrote: I visited the Words of A Feather website, and found a fun little quiz on the subject. I find the linguistic connections we are all making very satisfying, and take comfort in the fact that people actually care about the quirky history and development of our language. It also begs a peek into the future, and some educated guesses as to where our word futures lie. This page is covered with examples of "new" words, such as blog. Does anyone have suggestions for what comes next? --- Madeline wrote: "Words of a Feather" sounds like the kind of book every writer, budding writer, wordsmith or word wrangler can use. Actually, it's likely to be useful to those folks who use words on a regular basis. And Murray sounds like a fun guy. I think I'll put him on my list of "The three people I'd like to have come to my dinner party." We could pester him about the origins of everything served. Oh, I suppose it might be best just to buy the book. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Nameless characters, anathema to critics, lend some fun irony when they get tagged from the get-go: "When a nameless man (Siffredi) prevents a nameless woman (Casar) from committing suicide, she pays him to visit her at her deserted house and watch her 'where she's unwatchable.'" [ source] "Romantic rumblings start when a nameless man (Aaron Eckhart) meets a nameless woman (Bonham Carter) at his sister's wedding." [ source] "After his wife dies, the rough-cut and intentionally nameless 'man' (Jozsef Madaras) eventually coerces the 'woman' (Julianna Nyako) into doing his housework for a small remuneration." [ source] "We follow a nameless man (Nayef Fahoum Daher), content with his coffee and cigarettes, who tries to keep order in a rancorous neighborhood." [ source] "A nameless man (Alejandro Ferretis) travels from the city deep into the Mexican countryside, looking for a place to die." [ source] "One evening she meets a nameless man (Sam Neill) who, after coming back to her place, takes her hostage on his yacht." [ source] "A nameless woman (Kim Novak) plays a Madeleine Elster possessed by her ancestor." [ source] "This time, the action – well, inaction: our hero is at his most animated when rolling cigarettes – centres on a nameless man (Markku Peltola) who, having been beaten senseless, wakes up and finds himself among the homeless in Helsinki harbour." [ source] " Fight Club starts out, interestingly enough, about a nameless man (the Narrator, played by Edward Norton) who is a relatively successful employee of 'a major automobile manufacturer.'" [ source] "The film's opening credits flash with a frantic, dramatic score, and we are introduced to a nameless woman (Vanessa Redgrave) unable to sleep in a dingy third-world hotel." [ source] "This nameless man is played by Jean-Pierre Léaud." [ source] "Hope (Nadja Brand) and her young daughter are abducted and brought to a remote, terrifying forest by a mysterious and nameless man (Eric Colvin)." [ source] "So Laure lets a nameless man (Vincent Lindon) into her car to give him a lift." [ source] When an actor's name is unavailable, it's tempting to fill in the blank with a famous name ... "At the door is a guy who shall remain nameless, so I will call him KEITH RICHARDS for the sake of naming him something other than 'nameless man.'" [ source] ... or a deliberately mundane one: "The Narrator is a nameless man in the story (so let’s call him Jack)" [ source] Even when a nameless character is named "Nameless," naming him is still irresistible: "The movie begins with a nameless man (named Nameless — played by Jet Li) being delivered to a meeting with the king who is going to reward our hero for successfully killing the three people in his land who have been trying to assassinate the king for the length of his reign." [ source] Sometimes, even a scriptwriter can't resist naming a nameless character: "Tuco and the nameless man, who is called 'Blondie' throughout the film, are two con artists in cahoots." [ source] ___________ Jonathan wrote: This brings to mind that hard-cussing French film star, Nom de Nom. |

Page 70 of 74

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2025 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|