Go Out in a Blaze of Glory

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Corresponding-fiasco writes: "I must ask, all of the documents you post, where do they come from? What do you do? I've never seen anything like it in my life."

To quote Thelma Ritter in the film Boeing-Boeing, "It's not easy, you know?" We dedicate more hours a day than one might believe going through books digitized by Google, the British Library, and the Internet Archive, and we curate imagery that strikes our fancy, but then we take all said imagery into Photoshop to undo the various damage from the original scanning process: we correct contrast, sharpness, color balance, and trimming, and we try our best to erase digitizing artifacts that don't belong. And it's all just for the love of it. Granted we did include a particularly glamorous category of our finds in the book Ghost in the Scanning Machine, but the vast, vast majority of the pieces are just for here and our blog on Tumblr. Thanks for the appreciation! We suppose many folks just assume we stumble upon all this material, but in fact it's all hand-picked with painstaking care (with the marvelous side effect of boosting our time travel abilities).

Below, Prof. Oddfellow reveals one of the many tools* he uses to create Abecedarian — a mysterious genie bottle that arrived in the mail one day.

*This "one of the many tools" business is an homage to our lost friend Teresa of " Frog Applause" fame.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

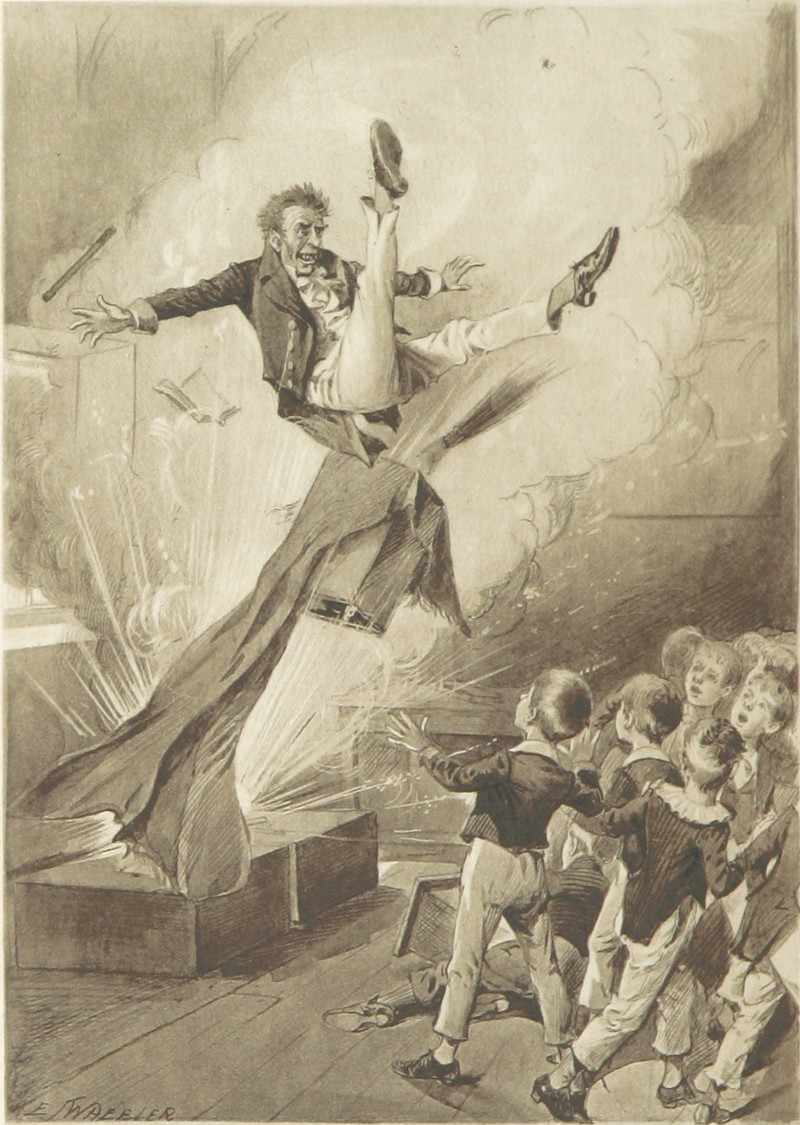

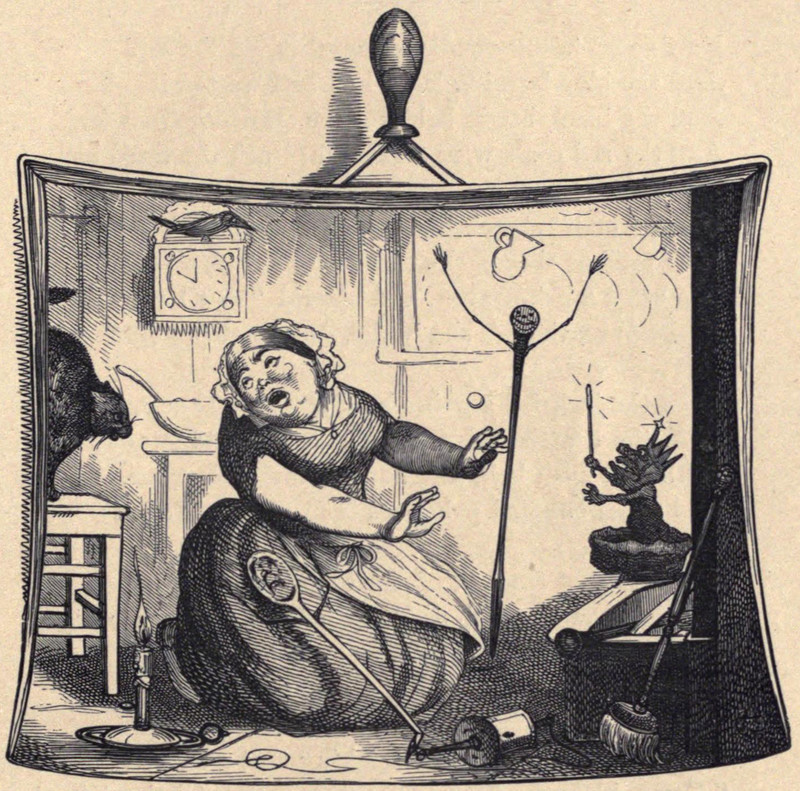

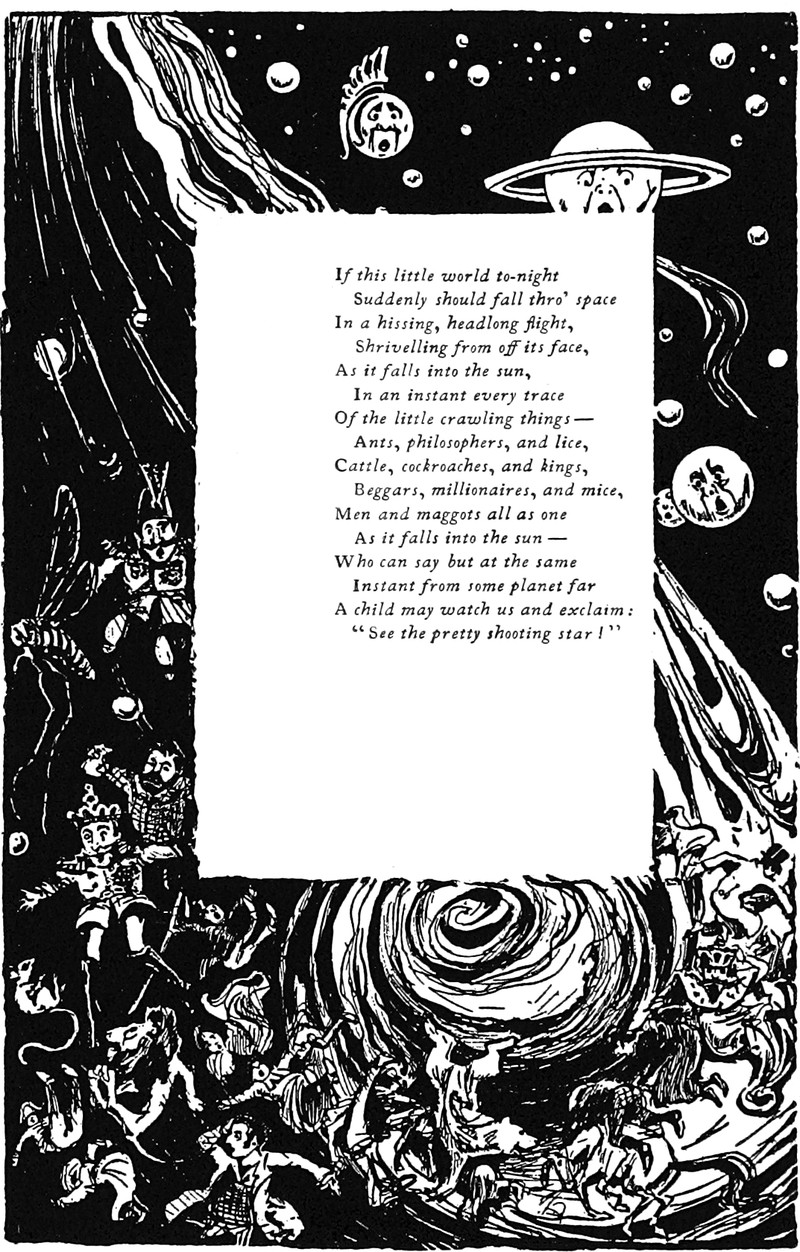

Illustration from Poets' Wit and Humour by William Henry Wills, 1860.

There's a macabre old fairy tale about an animated fireplace poker entitled "The Cinder King." The story's syntax is antiquated, but the plot is simple (if fantastic). A sobbing woman named Betty watches the fireplace, expecting either purses of money or coffins to fly out. It seems that Betty had recently been jilted by her lover, a tailor named Bob Scott. He took another bride to the altar, so Betty has resolved to woo the dark Cinder King for his riches. The clock is about to chime the hour of one, and the moment is described very evocatively: spent tallow-candle grease is seeping into the floor, a blue-burning lamp has wasted half its oil, a black beetle comes crawling from afar, and the red coals of the fire are sinking beneath their grate. Betty's life is clearly descending to the Underworld. When the clock strikes "one," it's not the cuckoo bird who sings but rather a grim raven. Betty's cat wakes up but keeps its claws retracted. The jack [which we here interpret as the figure of the man striking the bell on the clock] falls into a bowl as if it's time to dine. The earth trembles, and as if empowered by the fuel of Hell, the fireplace poker animates in a burst of flame. It shoots forth an enormous cinder that hisses three times like a serpent. Where the cinder lands there appears a large coffin containing a "nondescript thing." The thing croaks for Betty to embrace her true Cinder King, noting that three more kings (his brothers) are also waiting to greet her and will, at four o'clock, eat her. He explains that he and his "element brothers" have a feast and a wedding every night and that they devour each other's new wives. Betty begs not to wed, but cinders crunch in her mouth and cascade upon her head. She sinks into the coffin, strewn with cinders, never to be seen again.

THE CINDER KING

by Anon., c. 1801

Who is it that sits in the kitchen and weeps,

While tick goes the clock, and the tabby-cat sleeps, —

That watches the grate, without ceasing to spy,

Whether purses or coffins will out of it fly?

'Tis Betty; who saw the false tailor, Bob Scott,

Lead a bride to the altar; which bride she was not.

'Tis Betty; determined, love from her to fling,

And woo, for his riches, the dark Cinder-King.

Now spent tallow-candle-grease fattened the soil,

And the blue-burning lamp had half wasted its oil,

And the black-beetle boldly came crawling from far,

And the red coals were sinking beneath the third bar;

When "one!" struck the clock — and instead of the bird

Who used to sing cuckoo whene'er the clock stirred,

Out burst a grim raven, and uttered "caw! caw!"

While Puss, though she woke, durst not put forth a claw.

Then the jack fell a-going as if one should sup,

Then the earth rocked as though it would swallow one up;

With fuel from Hell, a strange coal-scuttle came,

And a self-handled poker made fearful the flame.

A cinder shot from it, of size to amaze,

(With a bounce, such as Betty ne'er heard in her days,)

Thrice, serpent-like, hissed as its heat fled away,

And, lo! something dark in a vast coffin lay!

"Come, Betty," quoth croaking that nondescript thing,

"Come, bless the fond arms of your true Cinder-King!

Three more Kings, my brothers, are waiting to greet ye,

Who — don't take it ill — must at four o'clock eat ye.

"My darling, it must be! do make up your mind;

We element brothers, united, and kind,

Have a feast and a wedding, each night of our lives,

So constantly sup on each other's new wives."

In vain squalled the cook-maid, and prayed not to wed;

Cinder crunched in her mouth, cinder rained on her head.

She sank in the coffin with cinders strewn o'er,

And coffin nor Betty saw man any more.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

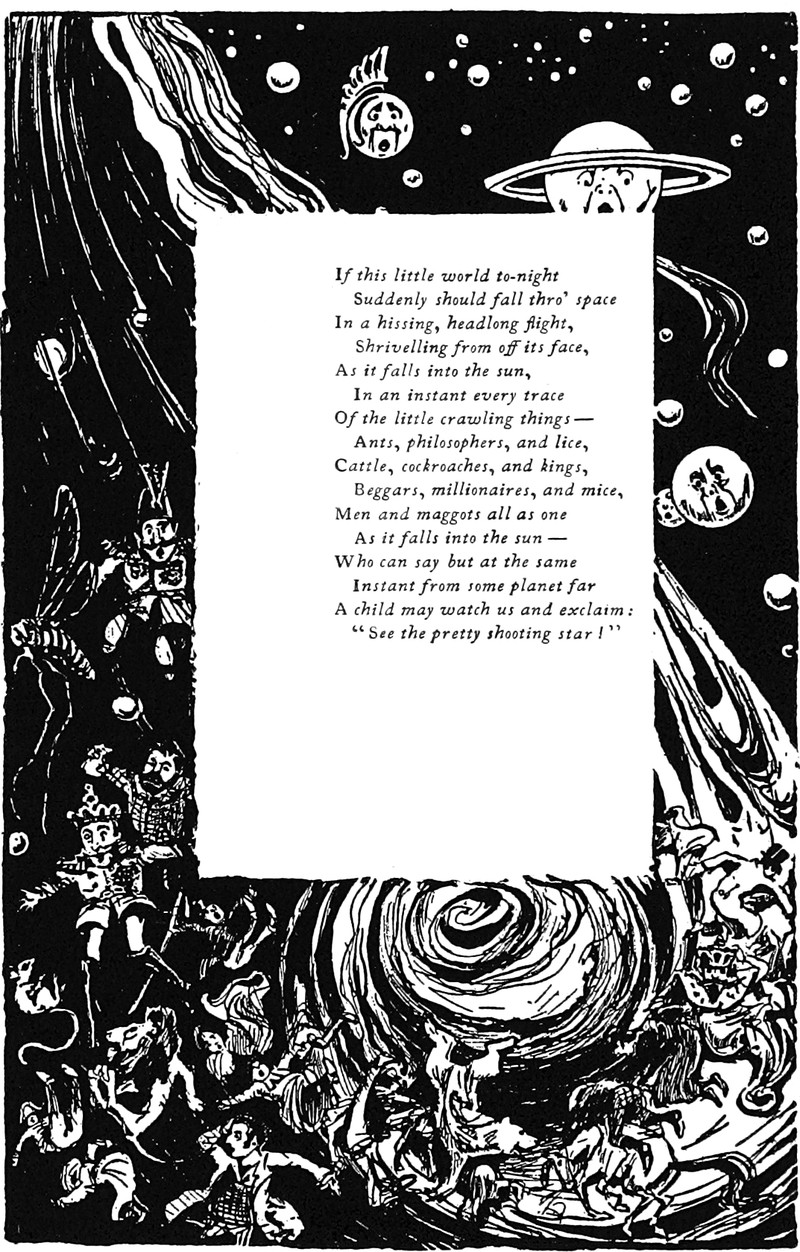

The text reads:

If this little world to-night

Suddenly should fall through space

In a hissing, headlong flight,

Shrivelling from off its face,

As it falls into the sun,

In an instant every trace

Of the little crawling things—

Ants, philosophers, and lice,

Cattle, cockroaches, and kings,

Beggars, millionaires, and mice,

Men and maggots all as one

As it falls into the sun—

Who can say but at the same

Instant from some planet far

A child may watch us and exclaim:

"See the pretty shooting star!"

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Thanks to USA TODAY's 10Best for featuring two of our photographs of La Cañada's Descanso Gardens. (See larger versions of the shots here and here.) |

Page 16 of 22

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2025 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|