|

|

|

|

|

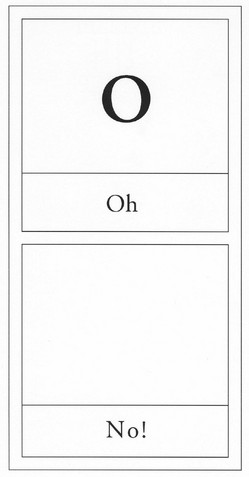

A gossip report quoted a source who "sounds like a teenage girl when she breathlessly relates (with all kinds of implied exclamation points and italic) that" so-and-so is inseparable from so-and-so. As if the idea of an "implied exclamation point" weren't delicious enough, there's mention of "all kinds" of implied exclamation points! My inner eye is feasting over an entire chart of implied explanation points, each variety clearly distinguished! As there was also mention of implied italic, perhaps each kind of implied exclamation point has an oblique variant. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

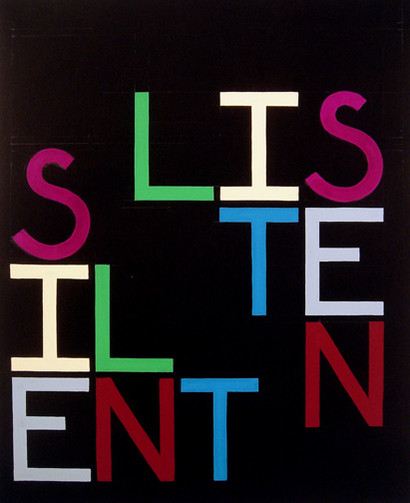

Luke Metcalfe, creator of a charming online anagram dictionary, suggests that "to some small degree we've been subconsciously shaping our language to make nice anagrams." He is referring to the huge number of anagrams that are surprisingly fitting, such as: eternity and entirety, backward and drawback, discern and rescind, demand and madden, comedian and demoniac, American and cinerama, aspirate and parasite, oldies and soiled, lust and slut. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Fun with quotation marks: Capital "A" and "Capital A" mean two different things in the context of this old architecture diagram. To learn the surprising answer, see my guest blog at the Society for the Promotion of Good Grammar. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Referring to the Dictionary of All-Consonant Words, Jonathan wrote: I visited Merriam-Webster online just now. Due to browser sluggishness, the consonants in the phonetic display of "bookkeeper" loaded first (presumably because the vowels, which are all represented with accent marks, are special characters). For just an instant, M-W was an all-consonant dictionary! |

|

|

|

|

|

|

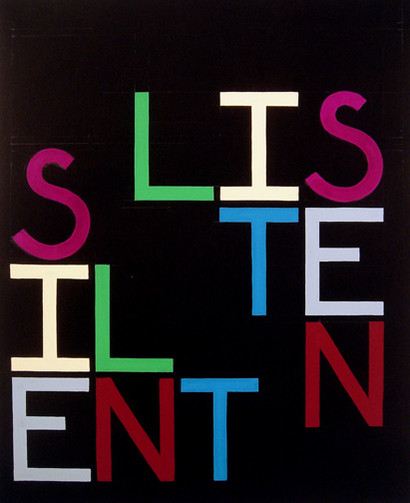

Tauba Auerbach's "Listen/Silent" anagram reminds me of a poem by Thomas Moore: When to sad Music silent you listen,

And tears on those eyelids tremble like dew,

Oh, then there dwells in those eyes as they glisten

A sweet holy charm that mirth never knew.

I like the idea of teardrops being a magical potion, glistening with enchantment of a shadowy (mirthless) yet sacred nature.

This anagram is by Tauba Auerbach and appears here by special arrangement.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

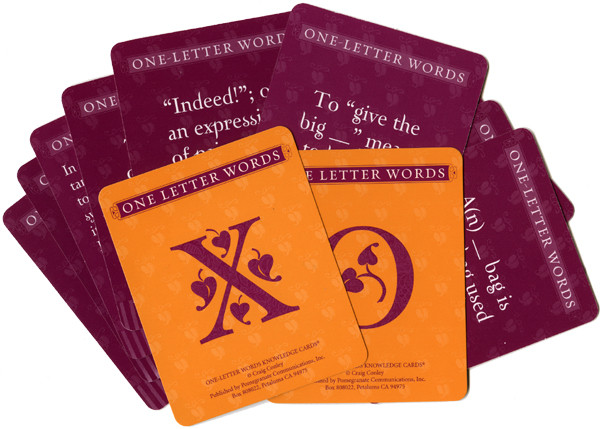

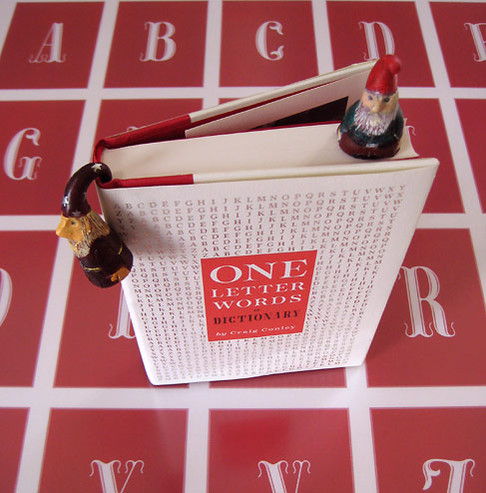

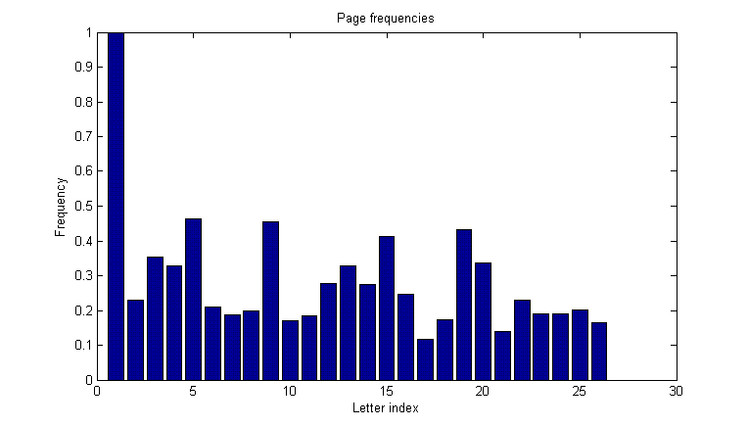

An engineer and armchair philosopher named Joel created this terrific bar graph of one-letter words that appear in Google's 8-trillion page index. "A" is the most common single letter on Google, followed by "e," "i," "o," and "s." At first I was surprised that "v" appears more often than the vowel "u," but then I figured it must have to do with "v" appearing as a Roman numeral. I like how the letter index goes all the way to 30, as if there are slots available for letters that only appear in leap years or something. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

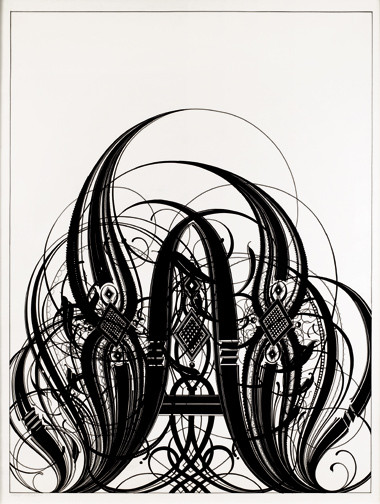

This is my all-time favorite quotation about one-letter words, probably because it encapsulates the concept of the microcosm: I was the only adult in the world who knew that ... a single letter of the alphabet would suffice for the entire encyclopedia. —Sandi Kahn Shelton, Sleeping Through the Night and Other Lies

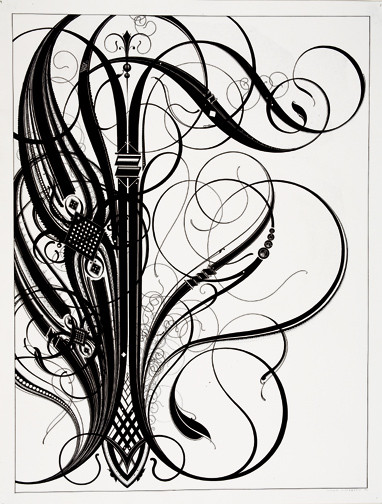

The illustration of the letter "I" is by Tauba Auerbach, whose alphanumeric work is endlessly fascinating.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

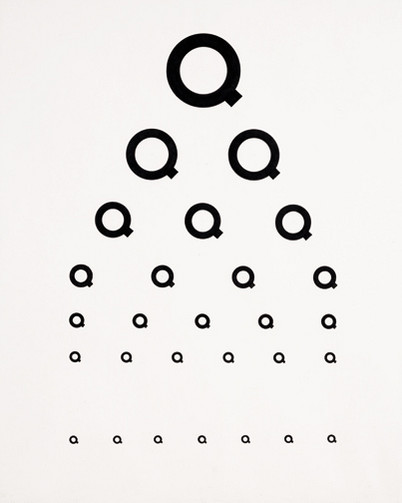

This is from Geof Huth's delightful "Analphabet" project. See the full sized image here, and see the entire collection here. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Did you see this Slate headline? What exactly is the dirty word in question? Whence the !@#$?

How a dirty word gets that way.

The headline has a couple of problems. Leaving out the colon between heading and subheading I can understand for clarity purposes [comedy drum roll]. But there's clearly a typo in the third word. Dirty words spelled with random symbols are simply nonsensical. My understanding is that letter substitutions were originally made carefully, not randomly. "Shit," for example, would have been written with a dollar sign for the "s", a pound sign for the "h," an exclamation mark or inverted exclamation mark for the dotted "i", and a dagger for the "t."

$#¡†

Such code is technically meaningless but clearly readable for content. Somewhere along the way, readers apparently weren't clever enough to decipher the obvious code and assumed that dirty words were to be represented by random symbols. And today even Slate boldly perpetuates the error, in bold type no less.

Granted, perhaps Slate meant to coin a new dirty word pronounced "IAHS." I'm game enough to try it out on occasion. Or perhaps Slate has something against the International Association of Hydrological Sciences, or the Institute of Applied Human Services, or even Indo-American Hybrid Seeds.

But that would be horseshit of an entirely different color.

---

J wrote:

Prior to the digital age, it was not uncommon for a typesetter to stumble

and upset an entire drawer of metal type onto the floor. The stream of

colorful language that escaped the typesetter's mouth at such a moment

came to be represented, in print-shop legend, by the chaotic heap of type

at the clumsy individual's feet. This may be the origin of the notion

that profanity is best represented by a random assortment of characters.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Inspired by Murray Suid's brilliant and humorous Words of a Feather, I went in search of the origin of flimflam and stumbled upon something more along the lines of a creation myth: A flimflam flopped from a fillamaloo.

—Eugene Field, "The Fate of the Flimflam," Poems of Childhood (1894)

--- Murray responds: Now I've spent a good chunk of my morning looking for a picture of a "fillamaloo" or even a simple definition. Nothing comes up on the Internet. What am I supposed to do--imagine it! Robert D Strock writes: As a youngster, (I am now 85 years old), an old-timer described a "fillamaloo bird" as a native of Panama. Its right leg was longer than its left, so it was a hill dweller that always walked clockwise around the hills. It could fly upside down and backwards, and did so in ever decreasing circles until it flew up its rear end. It then would scream "fillamaloo", which translates as, "Gee, it's dark in here." He didn't have a picture of the creature. |

Page 70 of 74

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2026 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|