|

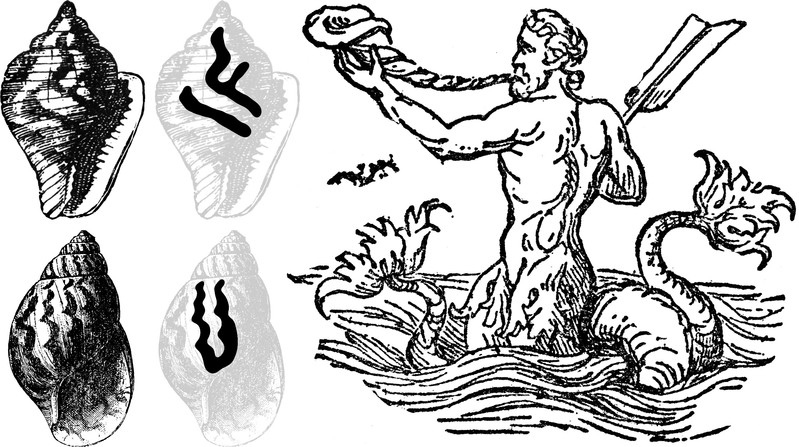

[This posting is in honor of Wilfried at Crystalpunk.) It is poetically said that when one raises a shell to the ear, one hears the ocean. Could it also be said that when one raises a shell to the eye, one reads poetry? In his masterpiece Doctor Faustus, Thomas Mann holds a magnifying glass to the "indecipherable hieroglyphics on the shells of certain mussels" and conchs, questioning whether Mother Nature expresses herself in an organized, written code, and whether ornament can ultimately be distinguished from meaning. Mann describes the calligraphy on a shell that practically begs to be understood: "The characters, as if drawn with a brush, blended into purely decorative lines toward the edge, but over large sections of the curved surface their meticulous complexity gave every appearance of intending to communicate something." The shell's calligraphy bears a strong resemblance to "early Oriental scripts, much like the stroke of Old Aramaic." But how is one to get to the bottom of such symbols? Mann admits that "They elude our understanding and, it pains me to say, probably always will." Yet this elusion need not be a source of discouragement. Mann explains that ornament and meaning are like conjoined twins: "When I say they 'elude' us, that is really only the opposite of 'reveal,' for the idea that nature has painted this code, for which we lack the key, purely for ornament's sake on the shell of one of her creatures--no one can convince me of that. Ornament and meaning have always run side by side, and the ancient scripts served simultaneously for decoration and communication. Let no one tell me nothing is being communicated here! For the message to be inaccessible, and for one to immerse oneself in that contradiction--that also has its pleasure." In other words, the shell calligraphy communicates a profound mystery, pregnant with meaning and delightful to behold. Mann admits that, "were this really a written code, nature would surely have to command her own self-generated, organized language," adding that nature's fundamental illiteracy is "precisely what makes her eerie." Mann's allusion to "early Oriental scripts" reminds us of the lost "shell" style of calligraphy discovered in Shang culture artifacts (14th - 11th centuries BCE). That ancient system of writing, more stylized than the early picture words, was brushed onto shells in vermilion ink. (For a full discussion of shell-style calligraphy, see Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting by Kwo Da-Wei, 1990.) In our collage below, we imagine King Triton conjuring the Platonic ideals of shell calligraphy.

|