|

|

|

|

|

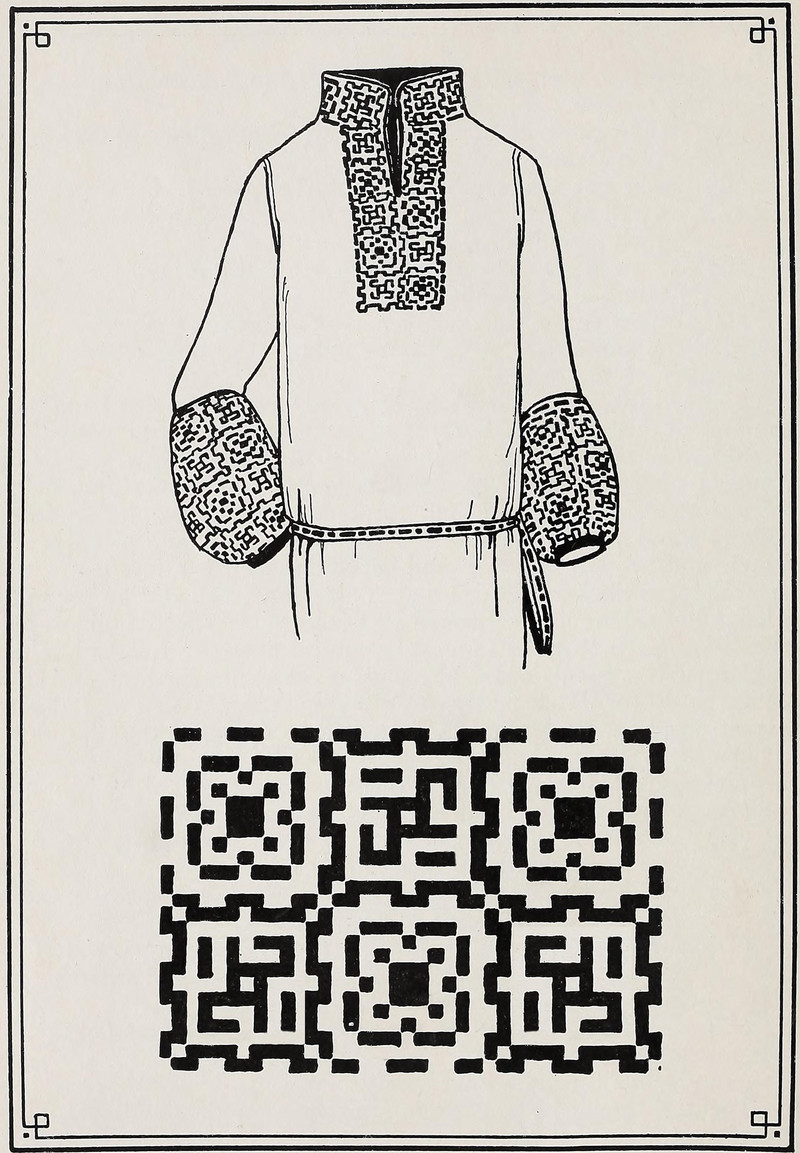

QR codes may have been invented in 1994, but they have decorated clothing long before. From Applied Drawing by Harold Haven Brown, 1928.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

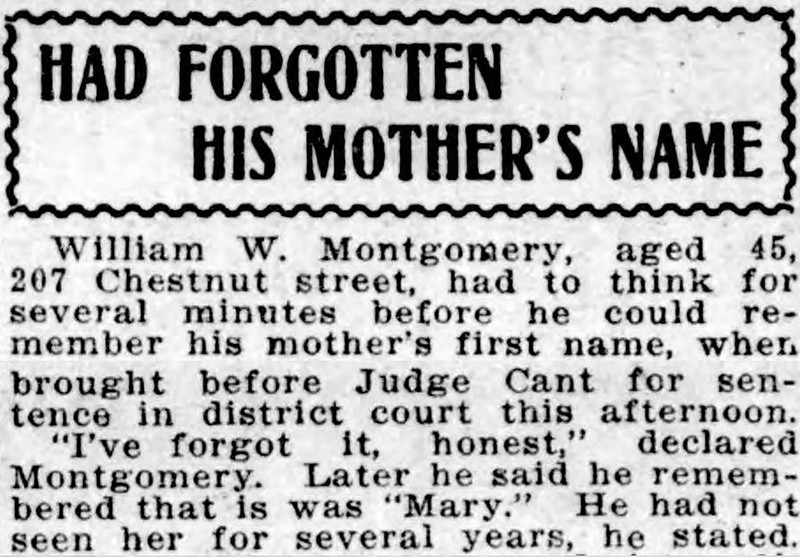

Here's a precursor to David Lynch's brilliant series On the Air, in which a character can't remember her mother's first name, which turns out to be Mary. In the Duluth Herald of 1912, a man forgets his mother's first name, which turns out to be Mary. His excuse was that he hadn't seen her in several years.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Before Wendy Carlos' synthesizer album Switched-On Bach (1968) and the disco of Hooked on Classics (1981), there was Jean Casadesus' versatility with boogie and Bach. From The Current Sauce, 1950.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The answer is supposed to be "They sell rabbits here," not "They sell cake here," but of course in The Wicker Man, it can be both. (Though, as Summerisle shopkeeper May Morrison says, ""Those are hares, not silly old rabbits. Lovely March hares.") From My Do and Learn Book to Accompany On Cherry Street by Russell & Ousley, 1948.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Two decades before Maxwell Smart talked into a shoe in Get Smart, this guy sang into his. The biggest difference is that this guy is actually singing about sanitary napkins. From The Ladies' Home Journal, 1945.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here's a precursor to the three doors of the Let's Make a Deal gameshow (1963), from The Gateway, 1962.

As we noted back in 2016, we call hogwash where we find it. There's a probability puzzle popularly called the "Monty Hall Problem." Entire books have been written about it, but we feel compelled to establish that it is pure nonsense. A contestant on Let's Make a Deal declares a choice from three doors (two hiding goats and one a new car). Then the host reveals a goat behind a door not chosen and suggests the possibility of switching to the other remaining door. On paper, this is a counterintuitive paradox in which the contestant is convinced of a 50/50 chance of success, when in fact switching doors offers demonstratively better odds. However, theorizing about the puzzle is ludicrous, and the considerable debate over the years is meritless, for the simple reason that a game show is a piece of theatre tantamount to a magic trick. The host of this purported gambling scenario obviously works for "the house" and knows where the car is hidden (presuming—which one cannot, in fact—that the car is not moved from door to door behind the scenes). Based upon subtle facial expressions and tones of voice (neither of which can be tabulated mathematically), the contestant wonders about being manipulated (with good reason). Creating truth tables or running simulations of possible outcomes is meaningless because there is no circumstance in the real world where any of the probability theory could possibly be relevant. There's a reason why the game show does not allow the contestant to simply walk up to a door and open it to determine the outcome. Just as a magician displays a deck to prove that it's well-shuffled (which it isn't, and that's why pains are taken to prove otherwise), the host opens a door with a goat as part of an elaborate psychological and theatrical presentation that "proves" the outcome is random. The outcome is not random on a television show designed to entertain. The contestant wins if the powers that be wish to give away a car during that episode, period. There is no other conceivable consideration (sorry, mathematicians and statisticians!). While we tip our hat to those who are capable of modeling possible scenarios ad nauseam, the "Monty Hall Problem" is no problem at all.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here's a precursor to the Heinlien novel and film Starship Troopers, concerning Earth's war against alien insects. From The Children's Newspaper, 1927.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Is the coat-wearing dog on the left a precursor to the cartoon character Mumbly? From The Children's Newspaper, 1953.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Here's a precursor to the bizarre singing weight scales in N. F. Simpson's astonishing One-Way Pendulum. "Singing to the gas meter." From The Children's Newspaper, 1927.

|

Page 3 of 71

> Older Entries...

Original Content Copyright © 2026 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|