How the Mysteries of The Prisoner Series

Are Clarified by The Tibetan Book of the Dead

Though there are seemingly infinite theories to explain the cult TV series

The Prisoner, we would suggest that the most elegant, comprehensive understanding is that the series deliberately illustrates the soul’s journey through the “Bardo” liminal state after death, as depicted in

The Tibetan Book of the Dead.

In the netherworld, when one is about to initiate a new birth, The Tibetan Book of the Dead’s first instruction for closing off a womb is to tranquilly meditate upon one’s tutelary deity until the deity melts away into clear light (Book II, p. 176). The Prisoner, in this still, is confronted by a choice: an egg or a Buddha.

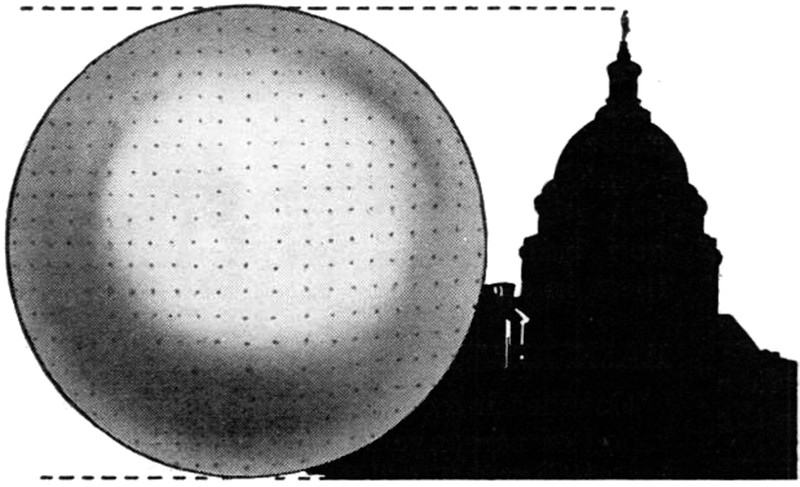

The Prisoner repeatedly resists fertilization throughout the series, prolonging his time in the liminal state until his true awakening. The green dome of Number Two’s office symbolizes a womb, and it also grandly depicts Tibetan cosmology: “Each universe, like a great cosmic egg, is enclosed within [an] iron-wall shell, which shuts in the light of the sun and moon and stars, the iron-wall shell being symbolical of the perpetual darkness separating one universe from another” (W. Y. Evans-Wentz, in the introduction to The Tibetan Book of the Dead).

In turn, the dome contains a smaller womb (symbolic of nesting rebirths) in the form the Ball Chair by Finnish designer Eero Aarino. Here we even see the womb chair holding an egg:

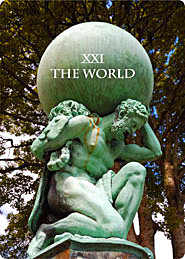

By the end of the series, the Buddhist cycle of rebirth calls so strongly that the Prisoner is sealed into a womb made of steel:

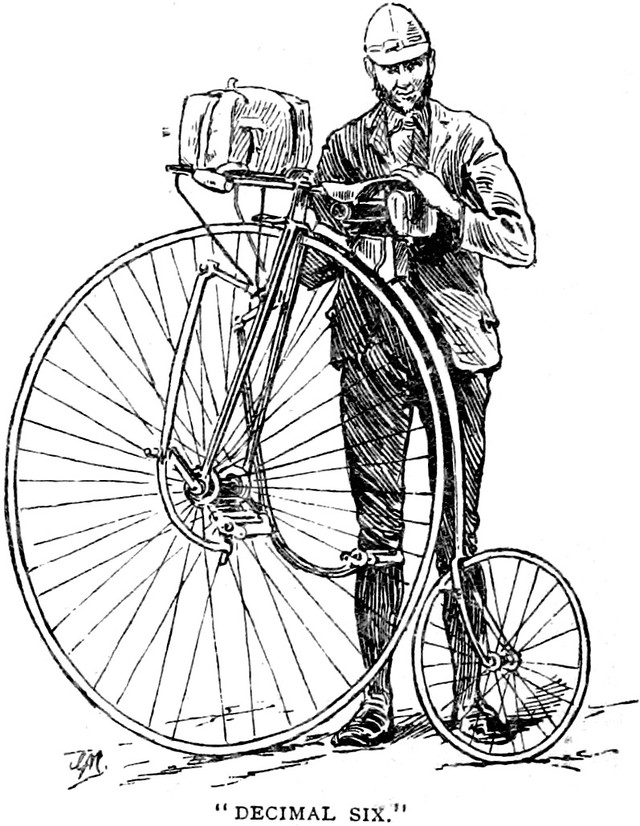

The beneficent and wrathful deities one encounters in the netherworld are, according to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, generated by one’s own psychology. “Fear not the bands of the Peaceful and Wrathful, Who are thine own thought-forms” (p. 204). In these stills, the Prisoner confronts his greatest enemy and warden, “Number One,” the numeral 1 doubling as the first-person pronoun. He removes the mask to discover himself.

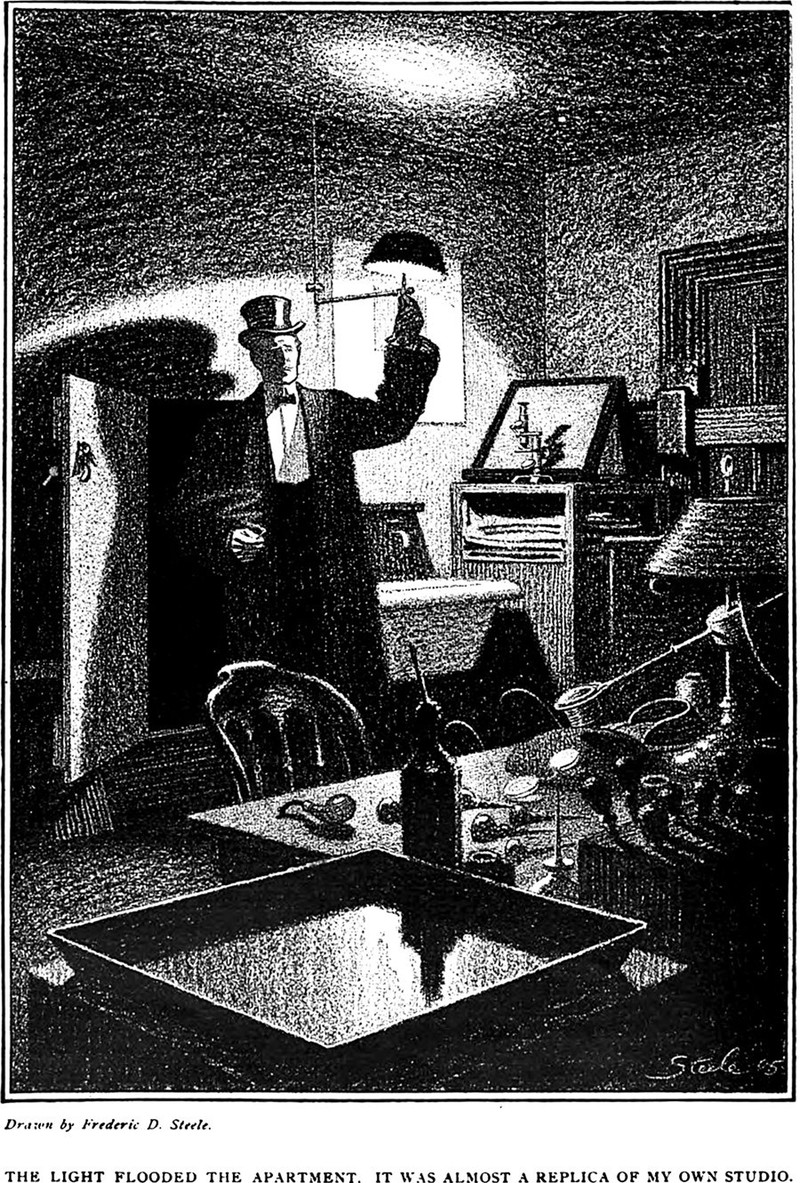

From the first episode, the Prisoner has been dead—he even goes down the classic long tunnel seen in near-death experiences:

And the events of his former life flash before his eyes:

However, he is not conscious of being dead. The externalized aspects of his mind, the “wrathful deities” in control of his netherworld prison, ceaselessly confront the Prisoner with his condition. Their eternal question, “Why have you resigned?” translates as “Why are you dead?” (In Tibetan as in Celtic lore, “no death is natural, but is always owing to interference by one of the innumerable death-demons,” as W. Y. Evans-Wentz notes in his introduction to The Tibetan Book of the Dead). Here is an explicit example of the Buddhistic understanding of the cycle of rebirth, with “resign” being a euphemism for “die”:

Throughout the series, we find the Prisoner being reminded that he is in the Bardo:

When the Prisoner becomes attached to this illusory existence, he is chastised in this Buddhistic way:

There’s a very subliminal hint in the title sequence of the series that the Prisoner’s entire journey takes place within his own consciousness: as he enters the subterranean parking garage to announce his resignation, there’s a flash of a sign: “headroom.” He’s confronting the underworld of his own headspace.

In this underworld described by the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the pangs of the deceased’s conscience rise up as a Good Genius and Evil Genius, personifications of a human being’s lower and higher natures:

The Lord of Death, who consults the Mirror of Karma (the memories of one’s good and evil deeds in life) is confronted repeatedly in the series. Here he is in one of his stern aspects:

Perhaps the primary guidance of the Tibetan Book of the Dead is which netherworld lights to avoid and which to follow. A dull yellow light lures one back into the world of humans, and such a light attempts to snare the Prisoner repeatedly:

A blue light lures one into the “Brute world” of stupid mentality:

A dull red light lures one into the realm of “hungry ghosts” who suffer insatiable addictions worse than humans do:

A green light lures one into the world of jealous warriors, the Titan-like “Asuras”:

A dull white light lures one into the worlds of angel-like “Devas”:

A smoke-colored light leads directly to the Hell-world:

No matter what, the Tibetan Book of the Dead promises that “the All-Good Mother … will come to shine … from eternity within the faculties of thine own intellect” (Book I, pp. 121-22):

As the Buddha says in “The Immutable Sutra,” “the phenomena of life may be likened unto … a shadow”:

As an aside, a near-subliminal detail in the title sequence recalls an insight by Philip K. Dick in his

Exegesis. Behind the car of the Prisoner’s pursuer there is a dumpster that says “St Mary’s.” As Dick put it,

"Lowly trash ... match folders ... tawdry commercials—therein lie the divine messages. … Therefore the right place to look for the Almighty is … in the trash in the alley."If you’ll be back, we wish you many happy returns …

… until you find your Way Out: