Found 6 posts tagged ‘tibetan book of the dead’ |

|

I Found a Penny Today, So Here's a Thought –

May 15, 2022 |

(permalink) |

|

|

|

|

Instead of dwelling on our regrets and failings (and thereby perpetuating our miseries), here's a suggestion to connect with the enduring influences of the things we did right:

"The present moment is the dividing-line between progression and regression. The present moment is the time when, by lapsing into laziness, even for an instant, you will experience constant suffering. The present moment is the time when, by concentrating with singular intention, you will achieve constant happiness. Concentrate your mind with a single-pointed intention. Resolutely connect with the residual potency of your vitrtuous past actions." — The Tibetan Book of the Dead, as translated by Gyurme Dorje (though overall we much prefer the older Evans-Wentz translation)

|

|

|

Hindpsych: Erstwhile Conjectures by the Sometime Augur of Yore –

August 27, 2021 |

(permalink) |

|

|

|

|

Two Otherworldly Books: Polar Opposites?

The two most famous mystical manuals for guidance through the Otherworld are, in staggering ways, diametric opposites. The Tibetan Book of the Dead was preserved by the living, its chapters kept intact over millennia by monks in monasteries. Contrariwise, the Egyptian Book of the Dead was preserved by mummies, its chapters scattered piecemeal (even as Osiris was dismembered?) and sealed for millennia in coffins and tombs. The Tibetan was meant to be recited to a corpse by a living undertaker. The Egyptian was meant to be read only by the deceased individual, in the afterlife. In the Tibetan, the soul navigating the afterlife liminality is a human who encounters deities and torments, judgments, and pitfalls, the book serving as a guide map to another incarnation. In the Egyptian, the soul in the netherworld is itself a divinity (indistinguishable from all deities), the book constituting "identity papers" that exempt one from any torments, judgments, or pitfalls on the way not to another incarnation but rather eternal providence. The Tibetan is read in whole and then retained by the living. The Egyptian is unread in fragments (as chapter 64 notes, "This composition is a secret; not to be seen or looked at ... by any man, for it is forbidden to know it. Let it be hidden") and retained by the dead. The Tibetan would have the soul disattach from memories of illusory experiences. The Egyptian soul, as a deity having been disguised as a mortal, is prompted to say, "That which I went in order to ascertain I am come to tell. Come let me enter and report my mission" (chapter 86). The Tibetan calls the soul toward realms indescribable by known language, while the Egyptian promises a perpetuity of familiar worldly food, bodily pleasures, landscapes, climates, planting and reaping, labor and recreation.Clerical (pun intended) errors by Egyptian scribes corrupted the book to the extent that varied copies of the same chapter are wildly discordant. It would seem that over the millennia the copyists did not understand the original texts, the original meanings having been lost at a very early date. The Tibetan, while similarly reproduced, is significantly less adulterated. Because the Egyptian copies were never meant for living eyes, the scribes' attention to detail naturally faltered (in other words, the accuracy of their work went unchecked). It was the opposite situation for the Tibetan scribes. As the Egyptian is significantly bastardized, translators are so often left to conjecture, to either fill or not fill the empty pools of textual lacunae, to baffle over the legitimacy of enigmatic hapax legomena. Yet there's a strange poetry to that — a book of metaphysical mysteries, not meant for living eyes, gathering further unfathomableness over time. (Somewhat ironically, Egyptologists seek "accuracy" of non-literal, possibly deliberately nonsensical esoterica and paronomasia. As translator Peter Le Page Renouf notes, the various chapters of the Egyptian Book of the Dead and other texts prove that "with reference to the details, free scope was allowed to the imagination of the scribes or artists." Though Renouf fastidiously checked his own guesswork, he perhaps needn't have been overly cautious. The Egyptian Book of Dead would seem to be unstuck in time and even unstuck in phraseology, like a text in an hallucinatory dream that morphs as the visionary tries to read it.)In short, the Tibetan (guarded at extraordinarily high elevations) is addressed to human beings, while the Egyptian (preserved at very low elevations) is addressed to gods.P.S. Interestingly, the judgment scenes in both books are so alike in essentials as to suggest a common prehistoric origin. The Tibetan's King of the Dead as judge corresponds to the Egyptian Osiris. Both books have a symbolical weighing. On the scales before the King of the Dead, black pebbles are weighed against white (symbolizing evil and good deeds). Before Osiris, the heart and a feather are weighed (conduct/conscience against righteousness/truth). In both books, a simian-headed figure oversees the weighing (the ape-headed Thoth in the Egyptian, the monkey-headed Shinje in the Tibetan). In both books, a jury of deities looks on, some animal- and some human-headed. The record-board that Thot holds corresponds to the Mirror of Karma held by the King of the Dead. The deceased in both books pleads innocence.

See Books of the Dead, a distillation of twenty-four books of the dead from around the world and across the centuries. Each book’s most intriguing, poetic, and useful revelations are painstakingly gathered.

|

|

|

I Found a Penny Today, So Here's a Thought –

June 2, 2021 |

(permalink) |

|

|

|

|

A Contested Prophecy, Literally True?

Skeptics cite Jesus’ promise that “this generation” will see the end of days as a failed prophecy, yet — extraordinarily — in the light of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, we can see Jesus’ words as very literally true. We’ll touch upon this, as we’ve not seen the insight discussed elsewhere. Mark 13:24-30 quotes Jesus as predicting that the sun and moon will be darkened, the stars of heaven will fall, the powers of heaven will be shaken, the Son of Man will appear in the clouds with great glory, angels will gather from the four winds, and — crucially — “this generation shall not pass, till all these things be done.” How can such a statement be literally true? It was literally true for each individual of that generation upon his or her death, for what Jesus described is parallel to the death experience detailed in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Skeptics don’t seem to see the individual trees for the forest. One at a time, human beings face the end of the[ir] world upon death. Light is extinguished and the soul navigates the turbulent “afterlife” environment of the Bardo, featuring terrifying winds and deafening thunders and deities and angels in the clouds.

Jesus makes an analogy four verses later of a man leaving his house and taking a far journey, and that, too, is parallel to the first day in the afterlife as described in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. (“Thou wilt see thine own home, the attendants, relatives, and the corpse, and think, ‘Now I am dead! What shall I do?' and being oppressed with intense sorrow, the thought will occur to thee, ‘O what would I not give to possess a body!’ And so thinking, thou wilt be wandering hither and thither seeking a body” [Book II, Part I]). Indeed, Jesus’ prophecy of the future can be understood as fulfilling itself for one person at a time, upon death. As the Tibetan Book of the Dead explains, when one’s earthly nervous system shuts off, the light of the sun, moon, and stars are no longer visible; only the “astral light” would be detectable to the deceased’s etheric being. In Book II, Part I of the Tibetan Book of the Dead, we learn that in the post-death Bardo realm, “The fierce wind of karma, terrific and hard to endure, will drive thee onwards from behind, in dreadful gusts. Fear it not. That is thine own illusion. Thick awesome darkness will appear in front of thee continually.” Yet “the embodiment of all that is wise, merciful and loving” will appear “as clouds on the surface on the heavens or a rainbow on the surface of the clouds.” It is the father of heaven (whom the Tibetans call the Manifester of Phenomena, who has dominion over worldly existence) appearing in the center of the sky, seated in a lion-throne (Book I, Part II), attended by angelic Bodhisattvas shining amidst a rainbow halo of light. Those not versed in comparative religion might be surprised to learn that Tibetans acknowledge that one might see Jesus in the afterlife. The Tibetan Book of the Dead explains that the “Great Body of Union ... will appear in whatever shape will benefit all beings whomsoever,” meaning that the godhead will take the form most appealing to the individual, such as Jesus to a Christian.

As a final note, concerning the overlap between Tibetan Buddhism and Christianity, Philip K. Dick explored at length in his Exegesis the “perpendicular path” to salvation that Christianity offers, and this same “Great Straight Upward Path" to enlightenment is made explicit in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. (Dick, conversant with both philosophies, preferred Christianity’s.) Both feature the peculiar doctrine of instantaneous spiritual emancipation without further suffering, and this doctrine underlies the entire Tibetan Book of the Dead. “Faith is the first step on the Secret Pathway,” explains a footnote in the Tibetan text, “Then comes Illumination; and with it, Certainty; and, when that Goal is won, Emancipation.” As in the ancient Egyptian symbolism of the sun-god Ra, it is the “hook” (as on a fishing line) of the “rays of grace” that catch and drag one perpendicularly from the dangers of the Bardo (Book I, Part II).

|

|

|

Hindpsych: Erstwhile Conjectures by the Sometime Augur of Yore –

March 30, 2020 |

(permalink) |

|

|

|

|

How the Mysteries of The Prisoner Series

Are Clarified by The Tibetan Book of the Dead

Though there are seemingly infinite theories to explain the cult TV series The Prisoner, we would suggest that the most elegant, comprehensive understanding is that the series deliberately illustrates the soul’s journey through the “Bardo” liminal state after death, as depicted in The Tibetan Book of the Dead. In the netherworld, when one is about to initiate a new birth, The Tibetan Book of the Dead’s first instruction for closing off a womb is to tranquilly meditate upon one’s tutelary deity until the deity melts away into clear light (Book II, p. 176). The Prisoner, in this still, is confronted by a choice: an egg or a Buddha.

The Prisoner repeatedly resists fertilization throughout the series, prolonging his time in the liminal state until his true awakening. The green dome of Number Two’s office symbolizes a womb, and it also grandly depicts Tibetan cosmology: “Each universe, like a great cosmic egg, is enclosed within [an] iron-wall shell, which shuts in the light of the sun and moon and stars, the iron-wall shell being symbolical of the perpetual darkness separating one universe from another” (W. Y. Evans-Wentz, in the introduction to The Tibetan Book of the Dead).

In turn, the dome contains a smaller womb (symbolic of nesting rebirths) in the form the Ball Chair by Finnish designer Eero Aarino. Here we even see the womb chair holding an egg:

By the end of the series, the Buddhist cycle of rebirth calls so strongly that the Prisoner is sealed into a womb made of steel:

The beneficent and wrathful deities one encounters in the netherworld are, according to The Tibetan Book of the Dead, generated by one’s own psychology. “Fear not the bands of the Peaceful and Wrathful, Who are thine own thought-forms” (p. 204). In these stills, the Prisoner confronts his greatest enemy and warden, “Number One,” the numeral 1 doubling as the first-person pronoun. He removes the mask to discover himself.

From the first episode, the Prisoner has been dead—he even goes down the classic long tunnel seen in near-death experiences:

And the events of his former life flash before his eyes:

However, he is not conscious of being dead. The externalized aspects of his mind, the “wrathful deities” in control of his netherworld prison, ceaselessly confront the Prisoner with his condition. Their eternal question, “Why have you resigned?” translates as “Why are you dead?” (In Tibetan as in Celtic lore, “no death is natural, but is always owing to interference by one of the innumerable death-demons,” as W. Y. Evans-Wentz notes in his introduction to The Tibetan Book of the Dead). Here is an explicit example of the Buddhistic understanding of the cycle of rebirth, with “resign” being a euphemism for “die”:

Throughout the series, we find the Prisoner being reminded that he is in the Bardo:

When the Prisoner becomes attached to this illusory existence, he is chastised in this Buddhistic way:

There’s a very subliminal hint in the title sequence of the series that the Prisoner’s entire journey takes place within his own consciousness: as he enters the subterranean parking garage to announce his resignation, there’s a flash of a sign: “headroom.” He’s confronting the underworld of his own headspace.

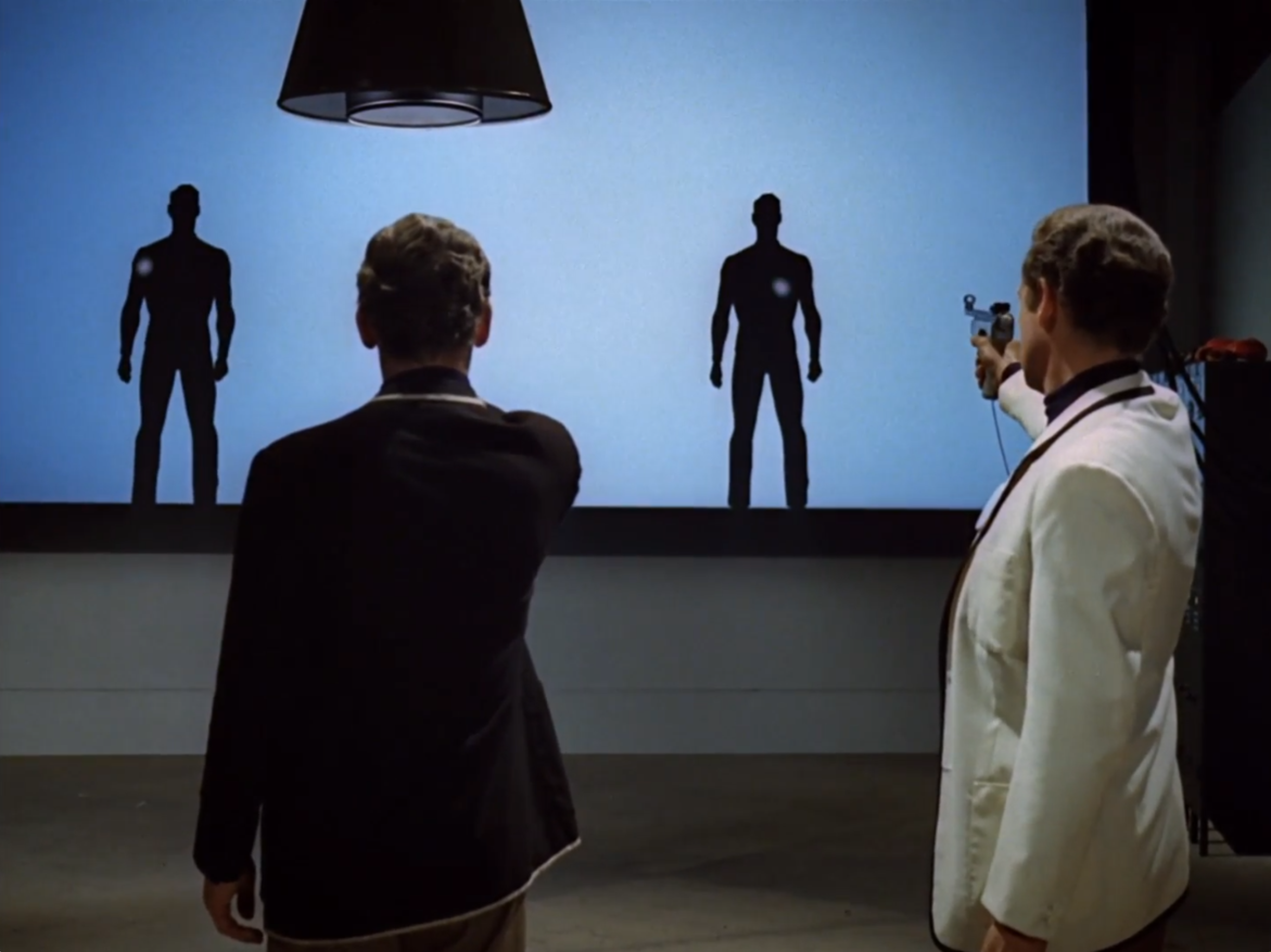

In this underworld described by the Tibetan Book of the Dead, the pangs of the deceased’s conscience rise up as a Good Genius and Evil Genius, personifications of a human being’s lower and higher natures:

The Lord of Death, who consults the Mirror of Karma (the memories of one’s good and evil deeds in life) is confronted repeatedly in the series. Here he is in one of his stern aspects:

Perhaps the primary guidance of the Tibetan Book of the Dead is which netherworld lights to avoid and which to follow. A dull yellow light lures one back into the world of humans, and such a light attempts to snare the Prisoner repeatedly:

A blue light lures one into the “Brute world” of stupid mentality:

A dull red light lures one into the realm of “hungry ghosts” who suffer insatiable addictions worse than humans do:

A green light lures one into the world of jealous warriors, the Titan-like “Asuras”:

A dull white light lures one into the worlds of angel-like “Devas”:

A smoke-colored light leads directly to the Hell-world:

No matter what, the Tibetan Book of the Dead promises that “the All-Good Mother … will come to shine … from eternity within the faculties of thine own intellect” (Book I, pp. 121-22):

As the Buddha says in “The Immutable Sutra,” “the phenomena of life may be likened unto … a shadow”:

As an aside, a near-subliminal detail in the title sequence recalls an insight by Philip K. Dick in his Exegesis. Behind the car of the Prisoner’s pursuer there is a dumpster that says “St Mary’s.” As Dick put it, "Lowly trash ... match folders ... tawdry commercials—therein lie the divine messages. … Therefore the right place to look for the Almighty is … in the trash in the alley."If you’ll be back, we wish you many happy returns …

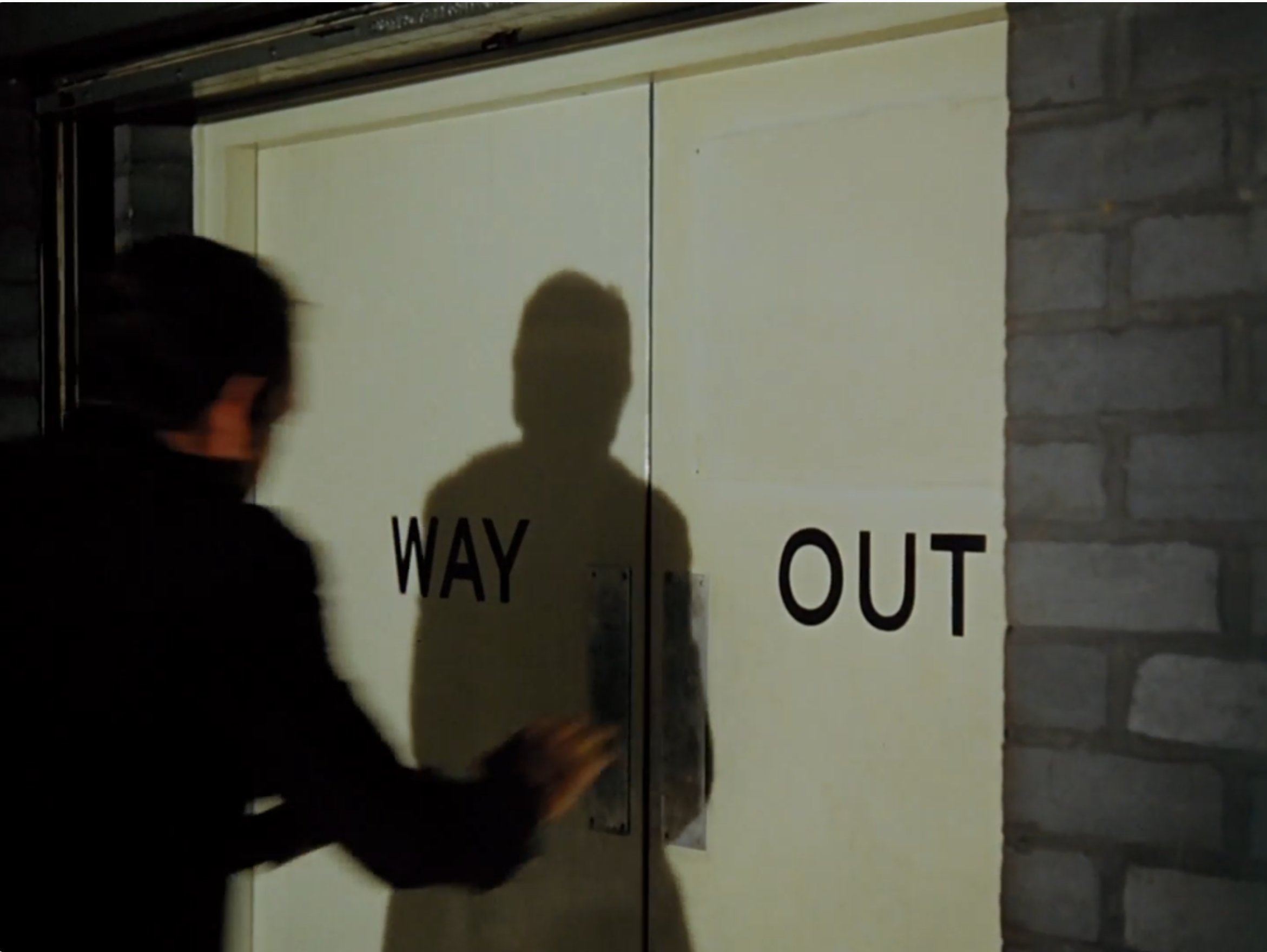

… until you find your Way Out:

|

| * Historians must reconstruct the past out of hazy memory. "Once upon a time" requires "second sight." The "third eye" of intuition can break the "fourth wall" of conventional perspectives. Instead of "pleading the fifth," historians can take advantage of the "sixth sense" and be in "seventh heaven." All with the power of hindpsych, the "eighth wonder of the world." It has been said that those who forget the past are condemned to repeat it. Therein lies the importance of Tarot readings for antiquity. When we confirm what has already occurred, we break the shackles of the past, freeing ourselves to chart new courses into the future. |

|

Original Content Copyright © 2026 by Craig Conley. All rights reserved.

|